In the late years of Empire, and early days of Christianity, there were monks who didn’t wash for fear of being overcome by lust at the sight of their own bodies. Some concealed their nakedness in outfits woven from palm fronds. One designed a leather suit that also covered his head. There were holes for his mouth and nose, but not, apparently, his eyes.

There was a monk who spent three years with a stone in his mouth to remind him not to speak. Another wept so hard, his tears dug a hollow in his chest. There were those who went about on all fours. St Anthony, one of the founders of monasticism, chose to make his home in a pigsty. St Simeon Stylites stood on a pillar for 37 years until his feet burst open.

What are we to take away from all this? First, that you should think twice before becoming a monk. Make sure you know what you’re getting yourself into. Second, that Christianity is a fundamentally masochistic religion. And third, that its self-punishing characteristics are a particular product of time and place: not only a reaction against Roman decadence but also, as Catherine Nixey points out in her clever, compelling book The Darkening Age, a response to the end of imperial persecution. The theory goes that, after the Empire adopted Christianity, some felt nostalgic for the enlivening fear of martyrdom, and compensated by metaphorically martyring themselves. This, then, is the essence of asceticism. It was a syndrome that St Jerome dubbed ‘white martyrdom’, to distinguish it from the red kind, which got you killed in front of a baying, paying crowd.

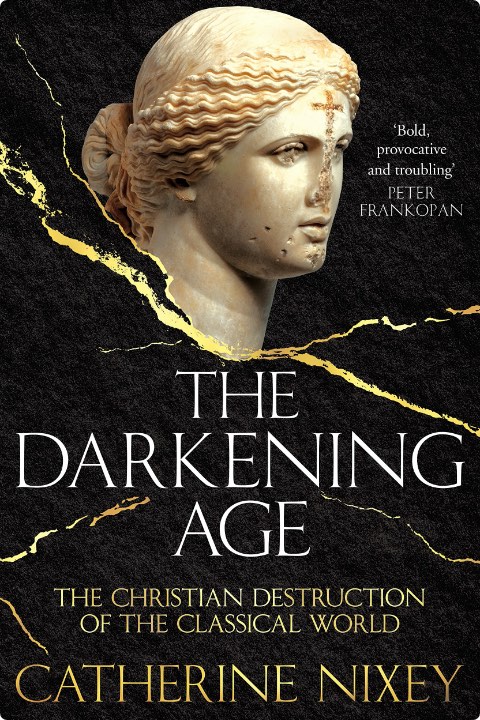

If there were persecution junkies who longed for a return to the good old days when Nero might set them on fire, there were also avenging angels. As its title suggests, Nixey’s book presents the progress of Christianity as a triumph only in the military sense of a victory parade. Culturally, it was genocide: a kind of anti-Enlightenment, a darkening, during which, while annihilating the old religions, the rampaging evangelists carried out ‘the largest destruction of art that human history had ever seen’. This certainly isn’t the history we were taught in Sunday school. Readers raised in the milky Anglican tradition will be surprised to learn of the savagery of the early saints and their sledgehammer-swinging followers.

Here are some darkening dates: 312, the Emperor Constantine converts, after Christianity helps him defeat his enemies; 330, Christians begin desecrating pagan temples; 385, Christians sack the temple of Athena at Palmyra, decapitating the goddess’s statue; 392, Bishop Theophilus destroys the temple of Serapis in Alexandria; 415, the Greek mathematician Hypatia is murdered by Christians; 529, the Emperor Justinian bans non-Christians from teaching; 529, the Academy in Athens closes its doors, concluding a 900-year philosophical tradition.

This gives some idea of the merit and remit of Nixey’s book. Also its demerit. What should be presented as conjecture is styled as fact. And when conjecture is admitted, the reasons for uncertainty aren’t given or gone into. Visit the Parthenon Marbles at the British Museum and you’ll see that the east pediment is particularly badly damaged — ‘almost certainly’ by Christians, the author tells us. But that’s about all she tells us, except to note that the marble was ‘likely’ ground down and used for mortar to build churches. This is a terrifically exciting aside: the greatest achievement in Greek art was pestled into cement for Christian construction work? How likely is this? How do we know? How could we know?

Yet perhaps it’s not fair to attack an exceptionally well written book by a journalist for being insufficiently academic. I’m in danger of coming across as a literary Theophilus, the temple-trashing cleric who Edward Gibbon described as ‘the perpetual enemy of peace and virtue, a bold, bad man, whose hands were alternately polluted with gold and with blood’. Or will I seem like one of those sad, God-addled wretches who rounded on Hypatia, the female Socrates, a heartbreaking early example of a woman who was killed for being clever?

In one of many instances where Nixey alchemises an anecdote with a few well chosen words, she describes how, while working as a teacher in Alexandria, this extraordinary heroine learned that one of her students was in love with her. It was her beauty, he mumbled, that haunted him. Hypatia left the room. A moment later, she returned with a handful of sanitary towels, flung them on the floor, and declared, ‘You love this, young man, and there is nothing beautiful about it!’ As Nixey exquisitely observes, the relationship ‘went no further’.

If you take home nothing else from this book, take home this: it’s a tactic to bear in mind, the next time you find yourself the subject of unwanted romantic attention.