This is what it’s like to be a writer. You become aware in your teens that you’re different. You’re more sensitive than other people. You feel more deeply. Then you start writing with a feverish compulsion. You scribble things in notebooks, on the back of your hand, on the backs of other people’s hands. You keep a sheaf of foolscap by the bed so that, if you wake in the night, your ideas won’t be lost to posterity. Publication ensues, then acclaim, followed by spinning-reel sales and, more often than not, the adulation of the opposite sex.

I’m kidding. Being a writer is nothing like this. To learn what it’s really like, pick up a copy of Chris Paling’s amiable, ambling literary diaries. For anyone not familiar with his oeuvre, his literary career – Paling has also held down day jobs as a Radio 4 producer and a librarian in Brighton – consists of writing quietly touching novels such as A Town by the Sea (2005) and Minding (2007). Critically, his books have earned approval from the broadsheets. Nick Hornby called After the Raid (1995) ‘enviably accomplished’.

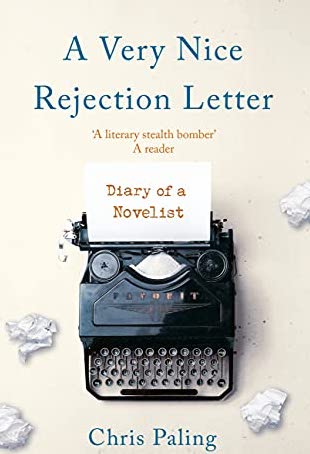

Yet somehow Paling has never made the big league of such near-contemporaries as Ian McEwan, say, or Martin Amis. One of the gentle pleasures of A Very Nice Rejection Letter is its portrait of the mild humiliations of being a mid-list novelist. Even the title is an example of one of these. It’s a phrase his agent uses to soften the blow when a publisher has said no.

Then there’s the gauntlet of school reunions. At one of these dreadful events, Paling comes across a crass-talking contemporary who delivers some unrequested feedback. He bought Paling’s novel Deserters (1996), about, he says, ‘some poofs in Brighton’. Unfortunately, he ‘couldn’t be doing with it’ and gave up before the end. ‘Bloody rubbish, it was,’ he concludes.

Paling doesn’t bear grudges. He describes the time he found himself doing a book signing in the same bookshop as Roddy Doyle. Doyle’s queue of fans snaked out the door and away down the street. By contrast, there wasn’t a single person at Paling’s table, not even someone standing there by mistake. ‘Nice bloke,’ Paling remarks of Doyle.

From time to time, we glimpse these bigger beasts loping past him on the plain. There’s a lovely description of the time when Paling stumbled drunkenly up to McEwan at a party and told him he was the reason he started writing. ‘No,’ McEwan replied suavely. ‘You’re the reason you started writing.’ Personally, I would have found this infuriating, but not Paling. He merely notes that, later that evening, he refused a lift from Kazuo Ishiguro because he was ‘feeling somewhat queasy’. He didn’t want to kick off his career by ‘blowing my chunks in the back of Ish’s new estate’.

The book has a three-act structure of struggle, despair and redemption. The first act (2007–8) sees Paling rowing against the negative currents in the life of a not-so-successful author. In the second act (2009), illness drives an oil tanker through his kayak. He develops diverticulitis, a grim condition of the gut that nearly kills him. Doped up on morphine, he gives us a fine hallucinatory account of his ailment, which, in its tribute to the selflessness of the nurses who cared for him, becomes unexpectedly moving: ‘When I ask them why they do it and work relentless hours for such a pittance they tell me they couldn’t imagine doing anything else. You can see in their eyes that they mean it.’

What about the author and his relentless hours of writing? With characteristic modesty, Paling attributes the impulse to a pathological need for attention, like a baby bellowing in its cot. Presumably, like the nurses, he couldn’t imagine doing anything else. In the third act (2019–20), we find our hero back out there in the melee, fighting, writing, hustling and even starting to suspect that the diaries we’re reading might, with a little judicious editing and perhaps the inclusion of some bridging text, make a publishable volume.

Like all diaries, these have the thinness of the present tense. There is more wit of the moment than wisdom of hindsight. Then again, that’s the sell. A Very Nice Rejection Letter is a completely authentic account of what it’s like to be merely reasonably good. This, after all, is the best many of us can hope for, whether we’re writers, accountants or makers of candlesticks.

Which brings me to an oddity in the way we choose our careers. When contemplating a line of work, we tend to imagine what it would be like to be hugely successful at it. So if we grew up in the late 1980s, say, and happened to be bookish, we might have thought to ourselves: yeah, I wouldn’t mind being a Mart or an Ian. Yet for most of us, the life of a Mart or Ian was as likely as that of a Martian. Bookish types growing up now should be wondering what it would be like to be a Chris Paling. In other words, they should be reading this book and deciding if they really mean it.