A bearded man in Mayfair, wearing a suit. That was what shocked me, stopping me in my tracks.

I’d been out of the country for a while. I came back for the weekend. And there he was, wandering along the pavement as if there was nothing remotely strange about his appearance. But there was, there really was. And it wasn’t just the fact that he was brandishing a full beard. It was the fact that, in addition to being bearded, he was also besuited, reasonable-looking and in his mid-twenties. In other words, there was absolutely no excuse for it.

It wasn’t an isolated sighting. Look around: you’ll see them everywhere. The clinching evidence is that David Beckham has recently been trying one on for size. The full beard is coming back. It’s happening.

The question is, why? What does it tell us? According to a recent study by Australian researchers, men grow beards as a “badge” of their sexual potency. Like many scientific studies, this reveals almost nothing we didn’t already know. As the paternalistically bearded Sigmund Freud demonstrated, you can claim, without risk of refutation, that men do everything in an attempt to get laid. The reasons for beardedness are a bit more complicated than that. Some, for instance, grow distracting “smog beards” to screen a facial deficiency (haphazard teeth, say, or an apologetic chin). Others sprout hippyish “trog beards” to imply that they live in caves. But what concerns us here is something more interesting than either: the “god beard”. A beard intended to convey the message that you’re particularly well equipped to interpret the world, because you may, just possibly, have had a hand in its creation.

Throughout history, beardedness has come and gone for a range of reasons. In ancient Rome, for example, the emperor Hadrian decided to defy the fashion of the times, which was to be clean-shaven, and instead cultivated a classic smog beard to disguise an unsightly birth mark. His subjects breathed a collective sigh of relief. Blunt razors, back then, made the morning shave an excruciating business. So they all followed suit and Rome became a bearded empire. Fast-forward to the 1960s, and trog beards enjoyed a surge of popularity during the hippy counter-culture, when to be hairy suggested, oddly enough, that you were in touch with your feminine side.

The god beard, however, suggests no such thing. The god beard is something else. I’ve spent the past year co-writing a lightweight introduction to some of civilisation’s greatest thinkers, and I’ve been struck by the fact that almost all of them sported heavyweight facial hair. In the 19th century, of course, everyone was at it. Partly, this was a habit that questing imperialists brought back from the Far East, where beards were seen as a sign of spiritual wisdom.

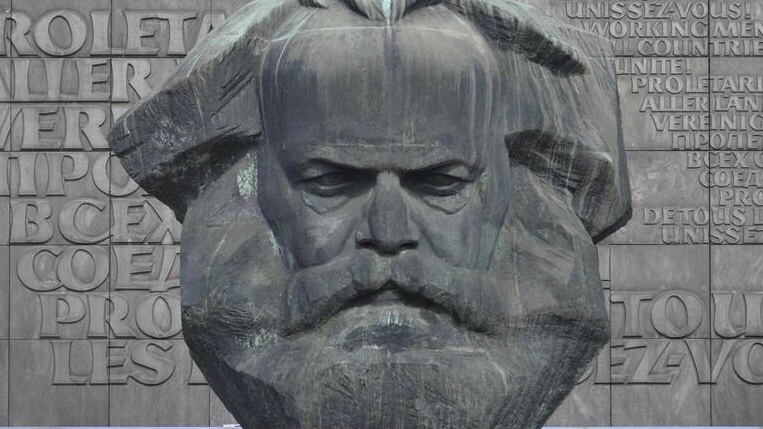

But also, it seems, it was because at the turn of that century seriousness and authority were coming under threat from every side. And no one was more keenly aware of this state of affairs than those who were most responsible for it. It was these mavericks – these missionaries and visionaries – who grew the most enormous beards. Karl Marx delineated a godless process by which, he was convinced, the bourgeoisie would inevitably be overthrown. While doing so, he grew a beard so marked and curly, a friend compared it to that of the Zeus of Oticoli: a bearded bust of the Greek king of the gods. From then on the hairy revolutionary proudly kept a copy at his London home.

Another of the great 19th century system builders was Charles Darwin, who industriously worked out a new interpretive method that would ultimately rival the major religions. Was he bearded? You bet he was!

As a matter of fact, if it hadn’t been for Darwin’s prodigious beard, it’s possible he wouldn’t now be the man we most associate with the theory of evolution. Other scientists were developing similar ideas at the time, but since Darwin was the hairiest, he was the easiest target for newspaper cartoonists, who sketched him to resemble a monkey, mocking the ridiculous notion that men might be related to apes. The image stuck. Darwin’s fame was sealed.

Darwin. Marx. Freud. Tolstoy. Morris. Spencer. Consciously or not, all were taking a leaf out of God’s book, creating a man in His image: namely, themselves. For if some intellectual titans were setting themselves up as rival gods, others grew their beards to pledge allegiance. The average Victorian beard declared conservatism, seriousness, dependability: desirable qualities in those times of social, spiritual and political upheaval. The trog beards of the 1960s, when you come to think of it, were also god beards of a kind. They conjured the spirit of Jesus rather than Jehovah. For that too was an age of revolution, when the old order was changing, yielding place to new. Now I’m not trying to claim, obviously enough, that the possession of a god beard automatically makes you a profound thinker or suggests that you’re on the point of constructing your own morality. Nor is this my way of announcing any plan to grow a thunderous god beard myself. (Unless I have a major change of heart, I shall be persevering with the wry designer stubble I’ve favoured over the past decade or so.) But what I do want to suggest is that the big beards that are currently blossoming on the streets of London are a sign of the troubled times we live in. We’re going to see a lot more, I predict, before this phase is over. It looks like we may need them.