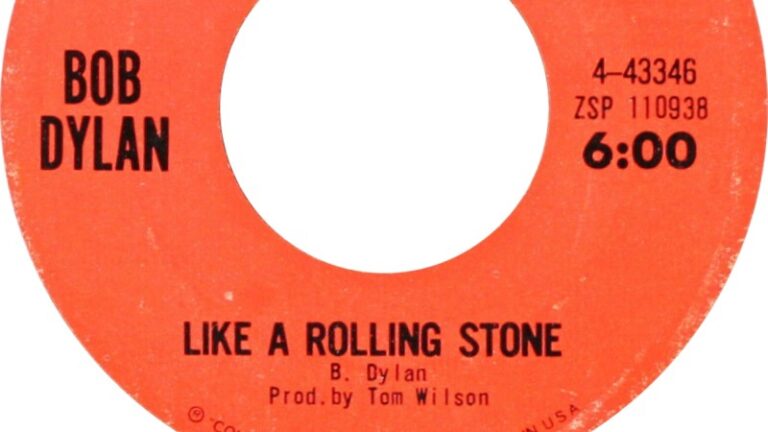

Once upon a time, a little Jewish kid from Minnesota wrote a song that was unlike anything anyone else was coming up with at the time. The record company (Columbia) didn’t like it. It was too long, they said: too harsh, too scarred. They were scared Bob Dylan would alienate his more sensitive, long-lashed fans. Yet when, against their worse judgment, Like a Rolling Stone was released as a single in July 1965, it became the biggest hit of his career. And when four sheets of hotel stationery on which the singer had scribbled those lyrics came up for sale in June, they were bought for a staggering $2m.

So how does that feel? How does it feel, to see your scrawls and doodles, yourscrivenings, fetch the same at auction as might be expected from a Picasso sketch? More to the point, how does it feel to be the mystery man — the unnamed “Californian fan” — who snapped up those spindrift pages at such a price? The answer is: it must feel nice. Even at $2m, it must feel like a steal.

Nathan Raab, president of the Raab Collection and an authority on this form of elevated hucksterism, told me the valuation of such a document is based on three criteria: rarity, historical significance and the “star power” of its author. Of the third of these, there is no doubt, in Dylan’s case. Nor of the first. So what about the middle one, historical significance?

A few years ago, Rolling Stone magazine put together its list of the 500 greatest songs ever. Number one was Dylan’s Like a Rolling Stone. Number two was (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction by the Rolling Stones. The first opens thus: “Once upon a time, you dressed so fine/You threw the bums a dime in your prime, didn’t you?/People’d call, say, ‘Beware, doll, you’re bound to fall.’/You thought they were all kiddin’ you.” The second includes the line: “Hey, hey, hey! That’s what I say!”

It’s hardly a fair comparison. The songs are doing different things, but that’s my drift. The rockfall of rhymes or half-rhymes in Dylan’s opening lines — four in the first two, three in the third — was a statement of intent, as was the nimble pairing of “didn’t you” and “kiddin’ you”. (One can picture him patting his own shoulder for that one.) This is before the flashing images of the later verses, as he unwinds the carnival of his cast list: the jugglers and clowns, the sinister “mystery tramp” with his vacuum eyes, and the down-and-out “Napoleon in rags”.

The bottom line is that Like a Rolling Stone rewrote the rule book as to what a rock song could do. Hey, hey, hey! That’s what I say!

As it happens, it’s what Paul McCartney says, too. “It was just beautiful,” he noted, recalling the day he first heard the new Dylan single. “He showed all of us that it was possible to go a little further.” First of all, literally. “It seemed to go on and on for ever,” McCartney recollected wistfully. In an era when the average hit came in at under three minutes long, Dylan’s clocked up a mighty six. There was also the lyrical specificity — the particularity, the peculiarity — of the song. While the Stones preened and postured in their tight trousers, and sang of pustular lust, Like a Rolling Stone addresses a girl who used to be well-off, sneering at the dregs and drop-outs, and asks her how it feels now she’s on her own, “With no direction home/Like a complete unknown/Like a rolling stone.” It’s a song that — like Lou Reed’s Perfect Day or the Police’s Every Breath You Take — reveals itself a far darker product at second glance.

Many have played the childish Guess Who? game (suitable for all ages) of trying to identify the girl in question from the singer’s address book. Edie Sedgwick? Marianne Faithfull? Joan Baez? Some have suggested Dylan addresses the song to himself. I love that, but it’s bonkers. As is my own pet theory, that the song is sung to a personification of Poetry.

That’s right, Poetry. You used to dress so fine, but you don’t talk so loud, now that the mystery tramp (public taste) has veered towards Napoleon in rags and the language that he uses. The last is an obvious reference to Napoleon Strickland, a Mississippi blues singer with whose work Dylan would doubtless have been familiar.

This is all hokum, of course, but it goes to show that the song lends itself to endless interpretations, which is a kind of greatness. And it articulates my theme that it showcases a level of verbal intricacy and invention that was once the province of poetry. It’s a call to all poets, telling them: put down your posies and pick up your picks. Music’s where it’s at.

Dylan said he’d been growing tired of the limits of pop-folk-rock, coveting the density of poetry and the dimensions of fiction. But after Like a Rolling Stone, he realised this had been a false dusk. He could do it all in music, and he would.

The manuscript that sold in New York lays before the eyes of anyone interested the creative process involved. As Raab put it: “It shows the master at the table, and gives the buyer a glimpse into how Dylan’s mind worked.”

Hearteningly, Dylan had to work at his words. He has said about Like a Rolling Stone: “It’s like a ghost is writing a song like that. It gives you the song, and it goes away.” You may infer from this that the ink flowed smoothly, but it wasn’t so. The manuscript shows he strove to incorporate “Al Capone” as a rhyme (say what?), not to mention “dog without a bone” (hmm). Also, he came nerve- rackingly close to responding to the question “How does it feel?”, trying out “Does it feel real?”, “Shut up and deal”, “Get down and kneel”, instead of — as, thank God, he did — leaving it ringingly unanswered.

Moon, June, spoon. It makes me like the man even more, especially when one spots, lower down the page, that he got bored and doodled. There’s a little hat. And a rather nice chicken.

This doesn’t diminish the song, which may not be poetry, or even (alas) about Poetry, but is certainly as good as. There’s nothing to explain the spine-shiver delivered by those three late lines, which turn the whole thing round and make it seem like Dylan feels, not resentment for the girl he’s been berating, but envy. “Go to him now, he calls you, you can’t refuse/When you got nothing, you got nothing to lose/You’re invisible now, you got no secrets to conceal/How does it feel?”

There’s no answer to that, except possibly, to borrow a phrase from Dylan’s garbled marginalia, “Get down and kneel”.