Ladies and gentlemen,’ Laurence Olivier declared in his clipped, semi-metallic tones to the audience at the Vic as he took his curtain call, ‘tonight a great actress has been born. Laertes has a daughter.’

The man playing Laertes to Olivier’s Hamlet on that evening in January 1937 was Michael Redgrave. The daughter was Vanessa, who would, as Olivier foretold, grow up to be a great actress. This vignette, you might say, contains all the majesty and mawkishness of the theatre. And a touch of its tawdriness, too. For rather than hurry to the bedside of his wife Rachel, Redgrave, it is said, slipped away instead to spend the night with his mistress, the incomparable Edith Evans.

Does the possession of genius necessarily bring with it a moral carte blanche? The question isn’t idle, since Michael Redgrave had genius, or something very near. The critic Kenneth Tynan liked to talk of a gulf between good and great acting performances. Olivier, he once wrote, ‘pole-vaults over in a single animal leap; Gielgud, seizing a parasol, crosses by tightrope.’ Redgrave, by contrast, ‘always chooses the hard way. He dives into the torrent and tries to swim across, usually sinking within sight of the shore.’

The consensus seems to be that Michael, a Cambridge graduate and published author, was too intellectual; too intelligent, perhaps, to be one of the truly greats. Not so Vanessa, whose mind moves instinctively, sometimes disastrously, in her emotions’ wake, but whose performances can astonish. Her apparently effortless turn in 2007’s Atonement, to give just one example, left the rest of that film looking like a sixth-form production.

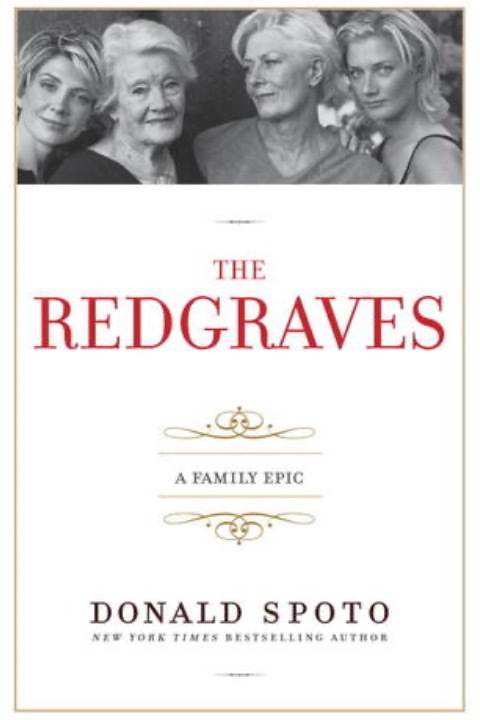

Theatrical biographies typically consist of a catalogue of performances, spiced with sexual shenanigans. To these themes, Donald Spoto’s multi-biography adds family life. No other family has devoted its life to acting in quite the way the Redgraves have. Michael’s parents, Roy and Daisy, were both actors. His children, Vanessa, Corin and Lynn, all trod or traipsed across the boards; as have their children, notably Vanessa’s daughters, Joely and Natasha.

The liberal allotment of talent has been equalled only, this book suggests, by the angst and heartache that attended it. The trouble can be traced back to Roy and his frantic infidelities. Married for 50 years, Michael was once described by the playwright Robert Bolt as ‘the most tortured man I ever knew’. What was it that consumed him? Simply, the fact he was, ‘to say the least of it, bisexual’ — as he finally confided to his son, before breaking down into quavering sobs. (The women in his life were mere blips on his sexual graph.)

Vanessa re-enacted her mother’s error by marrying a man with similar peccadilloes, the director Tony Richardson. ‘It’s a tragedy!’, Vanessa lamented, when she realised that their marriage was on the rocks. ‘It isn’t a tragedy,’ Richardson replied. ‘It’s life.’

I’m with Vanessa. Most of us don’t have to come to terms with a spouse sloping off in pursuit of an international sex icon. (In this case, the ‘other woman’ was Jeanne Moreau, who ditched Richardson soon after.) Nor, for that matter, are many of us burdened with a husband or father who gets his kicks at swimming baths, as Michael did, or who likes to do peculiar things with ping pong balls. (Google it.) Strolling across Leicester Square in 1954, Noël Coward saw that Michael (with whom he’d had an affair) and Dirk Bogarde were billed as appearing in the war film The Sea Shall Not Have Them. ‘I don’t see why not,’ Coward drawled. ‘Everyone else has.’ Spoto shares this well- known titbit, but is otherwise restrained when it comes to what he calls Michael’s ‘intimate life’.

The story of the Redgraves does resemble a tragedy, in the dramatic sense (much more than, say, the ‘epic’ of Spoto’s subtitle). Their fatal flaw has been their total commitment to their public lives, regardless of its private toll. Asked about her father, the 13-year-old Vanessa rather sweetly told a reporter: ‘We like it when he’s making a film, because then he’s home by tea- time.’ When her turn came, Joely would criticise Vanessa’s devotion to political causes, or as she put it, ‘her idea of changing the world but not being present for those around her’.

This plaintive note descends through the generations, moving one, in the end, to wonder if it was worth it. The answer depends on your attitude to theatre. Are you tempted to elongate those three syllables — the-ah-tah — in languid mockery? Or do you believe, as Vanessa does, that it’s ‘as essential to civilisation as safe, pure water’?

It depends, too, on how highly you rate the Redgraves as actors. And here, I’m afraid, Spoto doesn’t help us much. He writes smoothly and well. He certainly knows his stuff. But the best analyses of their respective gifts in this book are quotations from the actors themselves. To be sure, it isn’t easy to put into words what separates the good from the truly great, unless perhaps you’re Kenneth Tynan. It’s hard to say how or why Vanessa is able to walk across the water of that gulf, while her relatives languish in the shallows — or sink within sight of the shore.