A woman birthing bloated speckled eggs from her supernaturally swollen womb. Sushi screaming and squirming. A skull-shaped sweet, bearing the message, ‘I was you.’ Doubting yourself. Knowing you don’t love your girlfriend. Waking beside someone beautiful and new, only to notice a filigree of knife-scars etched across her breasts.

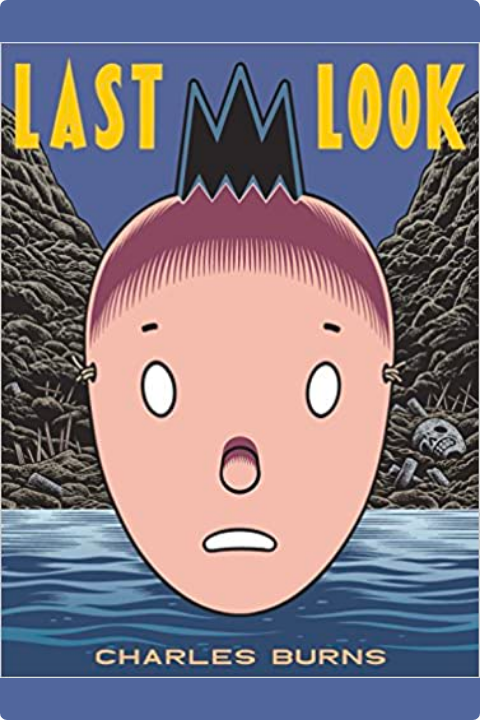

If, sensitive reader, these ingredients make you inclined to do a runner (your finger already hooked around the next, less distressing page), then go right ahead. Because Charles Burns’s Last Look (illustrated above) clearly isn’t your kind of book. But if you’re in two or three minds about this, then please hesitate, because I’m not 100 per cent sure, but I think it may be a masterpiece.

Burns, 61, is a big beast of graphic novels, and this is his major work of the decade. The story turns on the quest of a middle-aged depressive (you might call him passive defensive) to explore the stinking canals and catacombs of his psyche, and work out where it all went wrong. Crikey, you may again be thinking: sounds like a riot. And you’re right: this vision’s bleak. As Doug, our protagonist, sees it, the four ages of man are unwanted foetus, suicidal teen, adulterous adult and cancerous crank. But let’s face it, Hamlet isn’t a barrel of laughs either.

Neither is Last Look, with allusions linking Shakespeare’s inky-cloaked hero to Hergé and William Burroughs. As a love-hungry student, Doug declaims quirky riffs of verse from behind a Tintin mask. In nightmares, he becomes that mask. He calls himself Nitnit: an inverted, introverted Tintin, complete with perky quiff. In its surrealist scenes, this book comes into its own, weaving its motifs with disturbing skill. It manages things faster and more masterfully in graphic form than I can easily imagine in a literary equivalent.

The same, sadly, cannot be said for Love in Vain: Robert Johnson 1911– 1938. When, for a book, I recently compiled a catalogue of 75 key figures in the history of cool, the Mississippi bluesman — revered by Keith Richards, applauded by Eric Clapton — was at the top of my list. And by rights his mythic life should have made a doozy of a graphic novel. As any blues lover knows, Johnson is said to have learnt his skill with the six- string from the Devil himself. When he was just 27, the Horned One called in the debt, adapting his shape to cuckolded husband and spiking the singer’s whisky with strychnine. He died on all fours, the story goes, howling like a dog.

The brooding look of this book, which comes courtesy of the artist Mezzo, roughly does him justice. The thick-inked, woodcut-style panels succinctly recreate the back-breaking cotton-picking and risky rail-riding of Johnson’s youth, the spontaneous concerts in speakeasies and the ecstatic casual knee-tremblers that ensued. (This is quite a graphic graphic novel.) What lets the side down is the accompanying text by the French music critic J.M. Dupont, which is doggedly dutiful at best, and at its worst breaks out into howlingly bad doggerel. ‘Should we believe this story?’ it asks, for example, of Johnson’s Faustian pact. ‘Well, I know my mind. But best to leave it for later, I think you will find.’ Maybe it sounded meilleur in French.

One Hundred Nights of Hero by Isabel Greenberg is a reimagining of the Arabian Nights, in naif style, which will make the perfect present for your young daughter or goddaughter, assuming you’d like her to grow up hating men and believing it’s inherently preferable to be in a lesbian rather than a heterosexual relationship. Greenberg wouldn’t object to this description. She couldn’t, since it is clearly the aim of her book, which presents almost every one of its male characters as a coward or rapist or both, while the women are nearly all delightful. Although, of course, that’s an accurate rendering of the world as it is, I don’t think it’s nice or advisable to inform young readers of these facts at too tender an age. Which brings us finally to what may not be the strongest, but is certainly the strangest of these releases. New Year’s Day is Black (illustrated left), by the 71-year-old Norfolk watercolourist Nicky Loutit, is an experiment in autobiography which attempts to present a long and often unhappy life as it is actually remembered: not only in words or images, but by a scrappy combination of the two — non-chronological, incoherent, yet in glimpses that sometimes blast from her book with an eyeball-scorching force. It’s a bold and sobering work of art.