The last time I cried was September 1989. That was my first week at public school.

The reason I cried was that my allocated room-mate, a malevolent pixie named Toby Cox who later became one of my closest friends, had informed me that he ‘knew a lot of people’ at Harrow and he was going to tell them all that I was ‘a total dick’. I bawled. I blubbered, and a cord of saliva swung from my lower lip, as I begged for mercy. He refused. And I haven’t cried since.

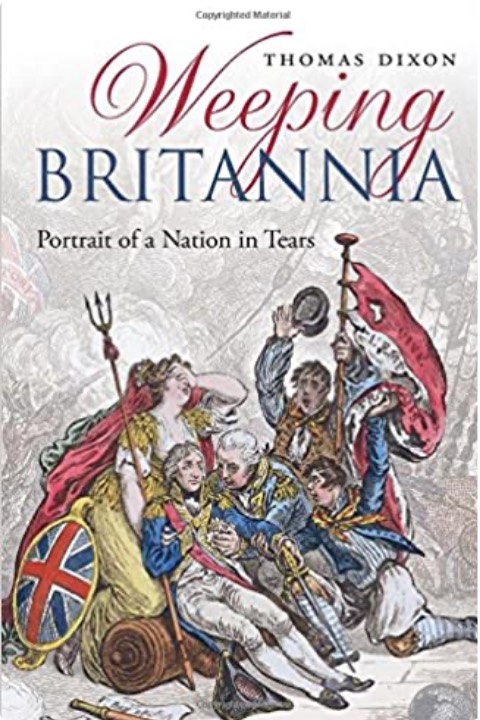

Not at the deaths of pets or relatives. Not at the break-ups of relationships. There’s something satisfying, I suppose, in fulfilling so completely a national stereotype. And I feel even more satisfied after reading Thomas Dixon’s excellent history of the British attitude to tears, which suggests that the stiff upper lip has been an even rarer, more fleeting phenomenon than I had imagined.

There’s evidence, going back centuries, of the British as rubicund beef- eaters, suspicious of pretension, prone to violence. But dry-eyed and stoical, not so much. True, Dixon finds a fore-echo in 16th-century Protestant scepticism towards Catholic histrionics. Hence our word ‘maudlin’, an allusion to Mary Magdalene, who misguidedly wept on finding Christ’s tomb empty.

Yet in the 17th century, we see Oliver Cromwell (not usually thought of as a softy) sobbing so prolifically at prayer that his tears trickled out under the closet door. And then, in the second half of the 18th century, came the Age of Sensibility, which found expression in the rise of the novel. As developed by the likes of Samuel Richardson and Fanny Burney, these ‘portable narrative performances’, as Dixon describes them, were, at least in part, devices for making people cry. In those days, it was the height of fashion to burst into tears at just about anything.

According to Dixon’s book — which is so well written, to the point and enlightening that there were times I almost wept — it wasn’t until the British empire reached maturity in the 19th century that we learnt to bite our lower lips to stop them wobbling, while keeping our upper ones as stiff as staple-guns. Awfully important, old chap, not to let the natives see you blub. That word ‘blub’, incidentally, was invented in the 1860s. A decade later, Charles Darwin observed that ‘Englishmen rarely cry’, contrasting this with the lachrymosity of our continental cousins.

Within a century, though, the upper lip began to twitch and quiver. Surveys suggest that by the 1950s we were as prone to sob in the cinema as now: that’s to say, about 40 per cent of men and 80 per cent of women admitted and admit to it. No dry-eyed scholar, the author confesses to being a ‘sucker’ for tear-jerking TV. Perhaps the classic contemporary example of the form is the ITV talent show The X Factor, which introduces contestants with brief biographical videos that are shamelessly designed to snip spinal columns, and reduce us all to carpet-thumping banshees.

And here we come to a theory that Dixon raises but doesn’t sufficiently explore: the idea that tears flow most voluminously at times of what he calls ‘momentous existential transition’. A wedding. A graduation. The funeral of a parent. As well as everything else wept about on these occasions, people weep at what they’re leaving behind, the death of their former selves.

The important thing here is the sense of transition. That’s why The X Factor, in its celebration of sobbing, has prioritised those videos, which emphasise the pain contestants have been through or the drabness of their backgrounds. The point is that to appear on the show and shine could change their lives forever. Yet — and here’s the rub — in order to sing, they have to keep it together.

Which brings us to another of Dixon’s insights, namely that few things are more likely to make us cry than the sight of someone else trying not to. Thus it was that, during an early instalment of this year’s series, after the soundly-built Filipina housewife Neneth Lyons had finished belting out ‘Somewhere’, and her face contorted as, beneath flared nostrils, her smile became wretchedly inverted, I found myself clutching the arms of my revolving chair in my little sitting room, my hair rearing on end, my knuckles milk-white with the effort of retaining self-control.

For this, you see, is the fear that haunts me: that one day I shall just start crying while watching an episode of The X Factor. And then, perhaps, I won’t ever stop.