In the mid-19th century, around lunchtime, a pale young man with an enormous beard could be seen in the British Museum reading room poring over piles of books about Mesopotamia. His name was George Smith, and this was his secret passion. Then, one day, a museum attendant remarked that it was a shame no one had bothered to decipher ‘them bird tracks’ — by which he meant the weird-looking scratches in clay tablets from the newly rediscovered ancient city of Nineveh. It was at that moment that something clicked in Smith’s head.

He set to it, decoding the cuneiform script to make a series of breakthroughs, culminating in one that excited him so much that, when he recognised it, he had to take his clothes off. The tablets were part of a long narrative poem, which, though predating the Old Testament by centuries, included a version of the story of the Flood. Soon the working-class autodidact was presenting his spectacular conclusions to a meeting of grandees, attended by none other than the prime minister, William Gladstone.

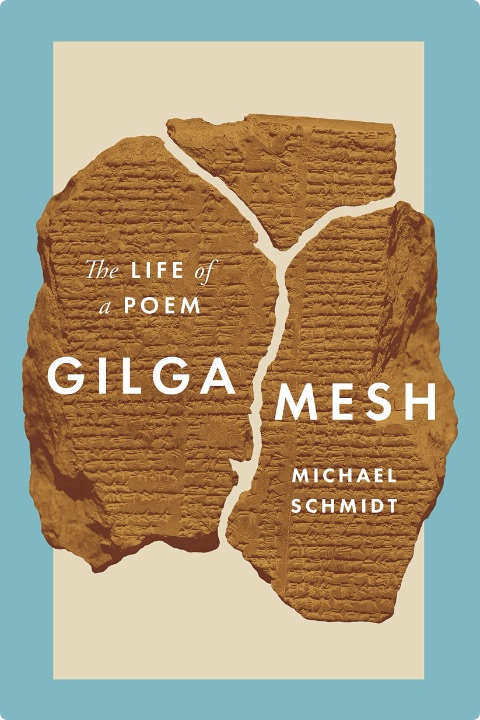

You won’t find much of this in Michael Schmidt’s new book about the poem usually known as the epic of Gilgamesh, despite the fact that it is the one Smith had identified, and despite the fact that Schmidt claims to be writing about its ‘life’ — how it began to be created a millennium before the Iliad (making it the oldest long-form literary work in history), how it was lost, and later re-found, and what impact it has had on world culture. You don’t learn how Smith, a former engraver’s apprentice with no archaeological experience, was sent to Nineveh by the Daily Telegraph to track down missing fragments of the Flood tablets — and did. Nor of how he died of dysentery in Aleppo, aged 36, leaving behind a wife and six children.

What do you learn? Oddly, a large part of this short book merely summarises the plot of the Gilgamesh poem. The godlike King Gilgamesh habitually rapes brides on their wedding night, so the gods create a rival to stop him: the hairy wild man, Enkidu. The latter is seduced and tamed by the holy prostitute, Shamhat. He fights Gilgamesh. It’s a draw. They become best mates and battle monsters together. Enkidu falls sick and dies, and the grief-stricken Gilgamesh wanders the world in search of immortality.

So far, so good, but you could learn this just as well by reading one of many English versions of the poem that are free online. Read warily, though. The author writes fascinatingly about how the ‘inadvertently colonial’ spirit of the 1960 Penguin Classics translation by N.K. Sandars, for instance, which has sold a million copies, distorts the tone. Egregiously, she introduces an ‘I’ into the opening (‘I will proclaim to the world the deeds of Gilgamesh’), mainly because a first-person is present in the opening of the Odyssey (‘Tell me, Muse, about the man’) and she wants her translation to be recognisably epic. Yet I was frustrated that Schmidt didn’t zoom in more on the ways in which this eastern work has been westernised.

He comes on enjoyably scornful of soi-disant translations by authors who can’t read any of the languages in which the Gilgamesh poem comes to us. Yet he doesn’t doubt that he himself, who also lacks these languages, is qualified to pass judgment in any detailed way on the relative merits of translators. His knowledge of Homer, so far as I can tell, isn’t based on reading those poems in the original. Nor does he say if any of the Arabic, Persian or Turkish translations of Gilgamesh are any good, or when they first appeared.

A poet, anthologist and man of letters, Schmidt embarked on his task by writing to 50 poets, asking what the Gilgamesh poem meant to them. We hear the thoughts of writers — many of them published by Carcanet Press, which Schmidt co-founded — from Britain, America, Israel and New Zealand, but not, for some reason, from Iran, Iraq, Turkey or Syria.

Anyone interested in Gilgamesh will get something out of this ‘little essay’, as Schmidt calls it, even if there are as many oversights as insights. But those new to the poem should first plunge into one, or preferably several, of the available translations. Maybe start with Stephen Mitchell’s hot, fanciful one; then try Sandars’s classic version for size; then knuckle down to Andrew George’s more scholarly and literal rendition. And revel in the eroticism, the colourful curses (‘May owls nest in your attic’), the heroics and the existential agonies.

Schmidt warns against seeking relatability in a poem created thousands of years ago. But I’m not so sure. When Shiduri the tavern-keeper advises Gilgamesh on how to lead a good life, she concludes: ‘Pay attention to the child who holds your hand, and give your wife pleasure in bed repeatedly.’ That’s something to aim for, whatever your millennium.