Once upon a time, there was an art scholar called John. He spent his days admiring marble statues, his nights in praying that he might be allowed a real- life statue as his wife. And in due course, he met a beautiful girl. She was a bit younger than him, but that was OK, because it meant she would be easier to control. Her name was Good Reputation, which seemed promising too. But on the wedding night, John got a nasty shock. For on lifting her trousseau, he found that, unlike the statues in the museums, Good Reputation had pubic hair. He was aghast. Unable to consummate the marriage, he channelled all his energies into his writing. This proved a mistake, for along came an artist who wasn’t so fussy, and John was left all on his own.

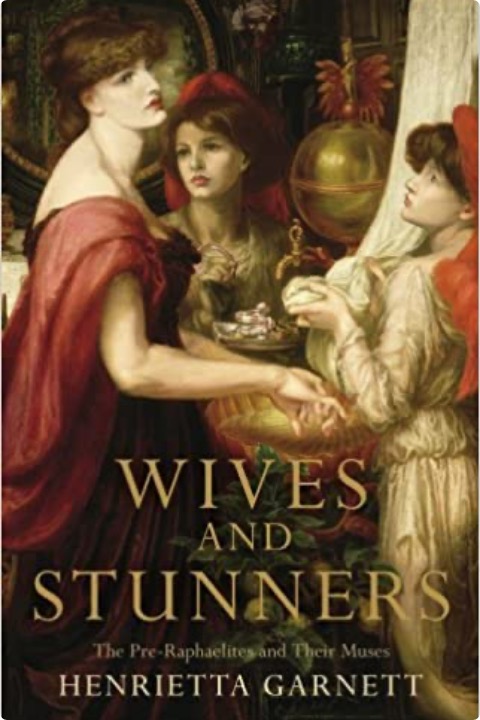

No fairy tale, this is the story of the marriage of the art critic John Ruskin, the author of The Stones of Venice, to Euphemia (known as Effie) Gray, who divorced him in favour of the painter John Everett Millais, causing the scandal of the 1850s. It forms the first panel, as it were, of Wives and Stunners, Henrietta Garnett’s engaging triptych of doomed mid-Victorian relationships. The second features Dante Gabriel Rossetti and his model and mistress Lizzie Siddal; the third, Edward Burne-Jones and his model and mistress Maria Zambaco.

These three — Millais, Rossetti and Burne-Jones — were arguably the greatest painters of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, that endearing if somewhat irrelevant enterprise begun in London in 1848, when a group of idealistic young men vowed to devote their art to verisimilitude and high moral purpose. In the event, they also spent a lot of their time loafing around the West End, trying to get laid. They dubbed their beautiful pick-ups ‘stunners’, asked them to pose, and soon after put down their palettes and pounced. The girls hoped they would get carried away and propose. It didn’t always happen.

The darkest pages of this book are haunted by the myth of Pygmalion — not only Ovid’s version, of the gynophobic artist who falls in love with his own sculpture, but also the version shaped by G.B. Shaw. A cynical bachelor teaches a working-class girl to be a lady, making her marriageable, if not in the end manageable. In Garnett’s words, ‘One of the strangest traits not only of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood but also of a certain strand of mid-Victorian society [was the desire to] transform the so-called ugly duckling into a swan.’ But it isn’t so strange, or not in the sense of unusual. It’s a standard male oppression fantasy; it was Ruskin’s fantasy. ‘Oh, why can’t a woman,’ one can imagine Ruskin exclaiming testily, ‘be more like a 15th-century sculpture?’ He used to jot down his wife’s failings in a little notebook he kept for the purpose.

What a bastard! one might think. Millais certainly thought so. Yet Ruskin was a more surprising, sympathetic man than this implies. He took a huge and innocent delight, for example, in shelling peas. It is one of the strengths of Garnett’s writing that she doesn’t take sides, or rather, she tends to take both sides at once. ‘When we married, I expected to change [Effie] — she expected to change me,’ she quotes the art critic in a frank and wistful letter to his father. ‘Neither have succeeded, and both are displeased.’ In the light of this pained awareness of his wife’s own disappointed Pygmalionism, one can’t help but feel rather sorry for the old booby.

Effie got her man, but she was ever afterwards snubbed in high society, which tormented her conventional spirit. That’s right. In Victorian England, if they didn’t get you one way, they got you another. Lizzie Siddal was a skinny, delicate-featured milliner’s assistant, who became an artistic icon when Millais painted her as Ophelia in 1851. That picture of the drowning girl, her dress billowing out, her pale face in shock, half-sensible of her situation, is for me the defining image of oppressed Victorian womanhood. It was also a glimpse of Lizzie’s future. After becoming Rossetti’s lover, she invested her hopes in his marrying her. But matrimony wasn’t his bag, and by the time he got around to it, she was hopelessly addicted to laudanum. She killed herself in February 1862, leaving a note pinned to her nightdress, asking him to ‘look after Harry’, her disabled brother.

It’s in moments such as these that Garnett’s book excels. Real feeling emerges, and a knack for colourful, engaged phrase-making. She’s less sure of herself, however, when it comes to the broader historical context; and she’s no Ruskin in her response to the art of the PRB. These bearded children looked backwards in time (the clue’s in the name), while 200 miles away, modern art was sidling towards Paris to be born. Yet by the intensity of their gaze they produced, despite themselves, some of the few genuine masterpieces of British art. Rossetti’s images of Lizzie, and later of Jane Morris, are astonishing, visionary, utterly his. Burne-Jones, by contrast, I’ve always struggled with — which is why I’m grateful to Garnett for making me look again.

He painted the Pygmalion myth in the late 1860s, and the last image of his series, as the painter kneels at the feet of the awakened statue, is about as sexy as a pair of John Ruskin’s underpants. Yet the model for the girl was one Maria Zambaco: a Greek heiress, who would become Burne-Jones’s lover and transform his art.

You only have to look at the difference between his ‘St George and the Dragon’ (1868), in which the anaemic maiden clasps her hands together as the hero pokes the unfortunate lizard with his sword, and ‘Phyllis and Demophoon’, which Burne-Jones painted just two years later. The latter, produced at the height of his affair with Maria, caused a scandal for displaying Demophoon’s genitals, for the sensuality of Phyllis’s clinging embrace, and for the fact that Burne-Jones’s mistress was clearly the model for the face not only of the woman but also of the man. The effect is a perverse aura of sexual ambiguity, a transferred solipsism, in which the only reality is that of the beloved.

As is often the way in these cases, everybody suffered, man, wife and mistress. Maria begged the painter to run away with her and live a carefree life among the isles of Greece. Burne-Jones balked, and the hot-headed Greek tried to fling herself into Regent’s Canal. His wonderful wife Georgie, to whom he had been so close at the start of their marriage, never recaptured the happiness of those early days. But the painter’s art entered a new phase. From being vague, it became keen. The bloodless became fierce and darkly inspired. For another example of his later style, see the extraordinary ‘Beguiling of Merlin’, which appeared in 1878. For once, as it turned out, the ‘statue’ had been not the model, but the artist himself. It was Burne-Jones who had been brought miraculously to life.