Frieda von Richthofen was fond of telling people that she was as interesting and important as her husband, D.H. Lawrence. Not everyone agreed. To the unconverted, the most extraordinary thing about her—putting aside her loud voice and immense capacity for smoking—was what might be called her freedom from sexual inhibitions.

This had its fans, naturally enough. Her lover Otto Gross, the schizophrenic Austrian psychologist, hailed her as “the woman of the future”. Lawrence (with whom she probably had sex within twenty minutes of their meeting, in 1912, despite the fact that she was married at the time) told a friend, “I could stand on my head for joy, to think that I have found her.” Less than two months after his death in 1930, she spent the night with his quondam friend John Middleton Murry, who wrote in his journal afterwards: “With her, and with her for the first time in my life, I knew what fulfilment in love really meant.” She seems to have been a lot of fun.

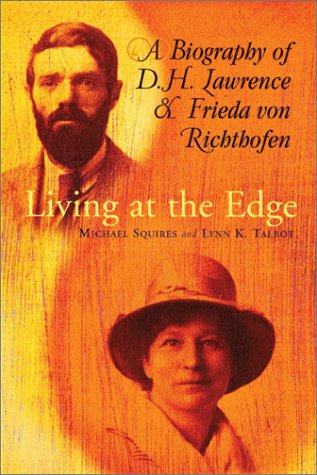

She was obviously more than that—a real inspiration to the men who knew her; to Lawrence, most of all. It is hard to imagine The Rainbow or Women in Love being written without her influence and support. I’m still not sure, however, that this justifies a joint biography like Living at the Edge, whose subtitle implies that the novelist and his wife deserve equal billing. The sixty dutiful pages covering Frieda’s life after Lawrence cannot help but be less interesting than what has gone before.

Another of the book’s flaws is the excessive reverence of Michael Squires and Lynn Talbot towards Lawrence, whom they describe as “a novelist of towering genius”. They are too willing to excuse or overlook his moments of fuzzy grandiloquence, his tendency to throw in the words “blood”, “phallic” or “living” whenever he wanted to sound truly mystical, and this weakens the force of their genuine critical insight. Moreover, the authors, who are themselves married, neither explore nor acknowledge Lawrence’s habit of beating his wife when one of their frequent arguments got out of hand. He had a love-hate relationship with most of the women in his life, going back to his mother. He led on, then let down, two early girlfriends, Jessie Chambers and Louie Burrows. Later in his life, there was an abortive affair with the painter Dorothy Brett. After he failed to get an erection, Lawrence blamed it on her, producing the frankly baffling accusation: “Your pubes are all wrong.” It is ironic, to say the least, that this priest of Eros should have been so clumsy a lover, and that the writer who prided himself on “sticking up for love between man and woman” was also an abusive husband, and an unfaithful one.

That said, Frieda was unfaithful first and more often. And yet the marriage lasted. As a celebration, which is what the book essentially is, Living at the Edge is excellent. Its hit-and-miss style is exactly that: in other words, as well as missing, it does sometimes hit, and hit hard. The authors probably have it right, for example, when they say in explanation of Lawrence’s peripatetic lifestyle, that he feared that “a fixed abode would subtly entrap him. The fact that he never saved the letters he received manifests the same impulse.” While many literary biographies contain little discussion of the works, merely naming them as they are published, as if the writing were somehow secondary to the life, Squires and Talbot provide a canny guide to Lawrence’s prodigious literary output: the novels, short stories, plays and travel pieces. They are not afraid to indulge in literary criticism. In the case of Women in Love, say, they illuminate the closely balanced structure of the novel (not a quality usually associated with Lawrence) and point out to what extent incidents and characters were taken from reality, and to what extent not.

The space devoted to these analyses, and the attention allotted to Frieda, have the result that parts of Lawrence’s life are thinly covered here. For example, the painting in oils that occupied so much of his time towards the end of his life is scarcely mentioned. As with the overlooking of his violent streak, one suspects this may have something to do with the authors’ Lawrence-ophilia (the novelist’s paintings were notoriously bad, so they omit to discuss them). They operate more by flashes of insight than by the accumulative effect of clear narrative. This is a forceful, occasionally gushing biography of a forceful, occasionally gushing writer.