‘As I was writing this book and trying to discover what it was about ….’ With his very first words, David Thomson pulls out the carpet from under himself, drapes it over his head, and runs towards the nearest wall. For what he’s admitting in this opening sentence is that, when he began work on this 578- page history of cinema, he had no idea what he was going to say. And man you have to be good to pull that off.

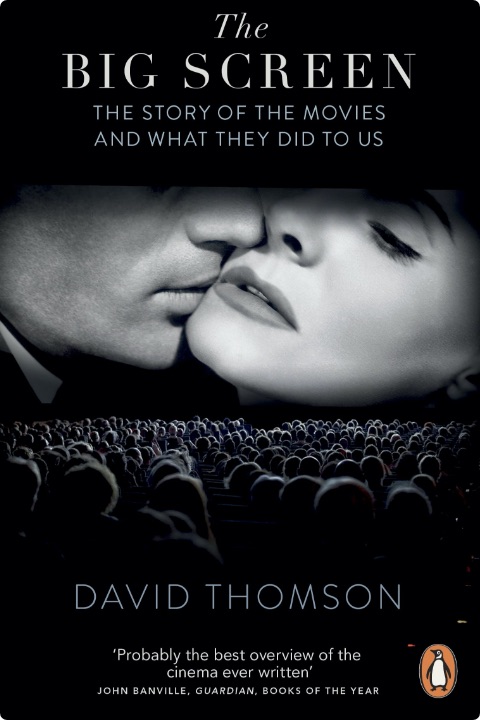

We live in an age of relativism, in which (arguably) assertions are often spliced with (this is only my opinion) apologetic parentheses. Yet books of this kind ought to be an exception. What we want is the Olympian overview or panoramic shot. They are pledged by Thomson’s subtitle, ‘The Story of the Movies and What They Did to Us’, and implied by his publisher’s blurb, which stakes his claim to being ‘the greatest living writer on film’.

The author himself seems to promise some accumulative heft when, four times in his prologue, he refers to a particular ambiguity of movies: the way they can inspire us to more vivid ways of living, or alternatively offer mere escapism. This, he declares, is the schizophrenic theme The Big Screen will explore. But it isn’t. It barely touches on it.

Instead, what we get is a decent, dogged tour of movie-making from its origins to something like the present day. We’re reminded, for example, of Eadweard Muybridge, who in 1877 came up with a way to photograph a galloping horse several times a second. We’re ushered through the silent era; assailed by the advent of talkies and Hollywood’s golden age; the nouvelle vague washes over us, surfed by Truffaut and Godard; then the so-called silver age of the Seventies, laced with the blood of mafiosi.

The structure of the book is defined more by films and film-makers than movements, say, or themes. This is unsurprising from our author. A venerable critic, Thomson is used to considering films singly. He’s known, too, for having created the magisterial New Biographical Dictionary of Film, which is treasured for its hissy wit and rich dismissal of some of Hollywood’s mega- stars. The latest edition, published two years ago, compared Keira Knightley to a crème brûlée (not in a good way), and likened Hugh Grant, with his public- school hair and droopy, distracted eyes, to ‘an incipient sneeze looking for a vacant nose’.

In The Big Screen, alas, there’s no evidence of this gift for phrase-making. Rather the opposite. ‘Scorsese looks at clothes, decor and male gesture,’ Thomson observes, ‘like a cobra scrutinising a charmer.’ Really? The photography of The Sweet Smell of Success, we’re told, resembles ‘the hide of a crocodile in the moonlight’. Does it? Eisenstein’s camera, meanwhile, zooms in on character actors, eager to get close to them ‘like a nose with cocaine’. What does that even mean? Elsewhere, the author applauds the ‘sly clatter’ of Fred Astaire’s tap-dancing. This phrase, like each of the others, has something in common with good writing, but is actually bad. Why sly? Why, for that matter, clatter? I’m being mean, but I don’t feel bad about it, because Thomson is better than this.

There are hints of it in the book, as when, after observing that Salvador Dali is now often derided as a madman and a charlatan, he adds unexpectedly, ‘as if those were not interesting and legitimate responses to our world’. He gives a sympathetic treatment, too, to Orson Welles, that interminable prodigy who left his promise, though not his waistline, unfulfilled. In a nice vignette, we learn how, late in life, the portly director used to drop in for lunch at a certain LA restaurant, and order steamed fish, to imply he was fit and ready for work. Then he’d go home and chomp a steak.

There’s a bittersweet section on Ingrid Bergman, whom the author describes, neologistically, as ‘a man-iser’. In the late 1940s, she sent a coy telegram to the director Roberto Rossellini: ‘If you need a Swedish actress who in Italian knows only “ti amo”, I am ready to come and make a film with you.’ The subtext of this message, of course, was that she was ready to do something else with him as well, and in due course the two began an affair. They became, in a sense, the Burton and Taylor of their day, except that the scandal of their love (both had been married when they met) slowed their trajectory, instead of accelerating it.

What should this book have been about? That’s not really for me to say, but it could, for example, have explored the effect Hollywood has had on popular notions of love, the two-hour format leaving little room for anything but an endless insistence on that value: love, love, love, like the drone of a Beatles chorus. This is especially true of big-budget, middlebrow fare, and if Thomson had really wanted to assess what films ‘did to us’, he might have devoted less time to the arthouse, and more to the multiplex. He might have considered the impact of movies on what the historian J.M. Roberts has called the single biggest difference between the present and past: namely, the awareness of the possibility of change. Cinema has encouraged people in unprecedented numbers to imagine what it would be like to be someone other than themselves. This can be, and has been, positive. But it can go the other way too, conjuring the fantasy of filling the shoes not of the characters on the screen, but of the actors playing them.

So the dream became first to be a movie star, then merely to be famous. Now it’s simply to be seen. I am seen, therefore I am. This is the message of Facebook and the ubiquity of camera phones. This is the buzz of the limelight.

Arguably. Yet the author, who is now in his seventies, doesn’t argue it, or much else for that matter. He has produced a stop-start book, with little sweep or continuity. And it leaves one wondering how they have affected him, all these film reviews he has written over the decades, and which he still writes very well. As Cyril Connolly once found when it came to assessing literature, Thomson has mastered the short form, but he struggles to sustain that quality over the duration of a book. This is only my opinion, but I suspect that the untold tale behind The Big Screen, its unspoken subtitle, might actually be ‘a story of movie criticism, and what it can do to a critic’.