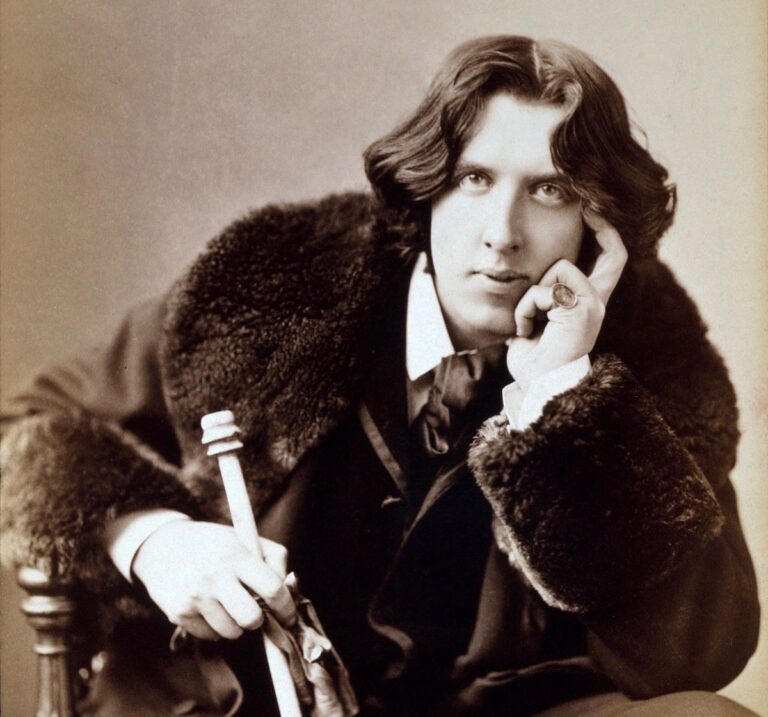

“Man is least himself when he talks in his own person,” Oscar Wilde once remarked. “Give him a mask and he’ll tell you the truth.”

In 1895, he was given a mask. Among the prison clothes the writer received, after he was sentenced to two years’ hard labour for having sex with men, was something that was known as a Scotch cap. It was a leather cap with a long peak, which slanted downwards to cover the face. The idea was to prevent prisoners from striking up friendships with one another.

“Even in prison, a man can be quite free,” he had written in an essay. Now he found himself incarcerated during a time of astonishing brutality in the British penal system.

Today marks the 125th anniversary of Wilde’s release from Reading Gaol. The prison, which closed in 2014, is the focus of a campaign to turn it into an arts centre, with the support of everyone from Banksy to Kenneth Branagh. What better moment, then, to explore what Wilde went through during those two years?

As well as the Scotch cap, his garb included a suit of prison clothes, which were newly cut for him owing to his unusual height. These were covered in broad arrow marks to indicate that he was now property of the crown. The tradition is said to have been introduced, fittingly enough, by the poet Philip Sidney, when he was Queen Elizabeth’s Master of Ordnance.

In the mid-19th century, after Britain stopped sending convicts to Australia, there were fears of a growing criminal class at home. Accordingly it was decided that prison should be a frightful experience designed to deter people from crime, rather than an improving one to reform them. That led to what was called the Separate System. Prisoners were kept in one-man cells for 22 hours a day. When they emerged for one hour of chapel and one of exercise, they had to wear the Scotch cap. Talking was forbidden.

This was torture for anyone. Solitary confinement, which it almost was, is now classed as such. For Wilde, who was the greatest talker of his age, it must have been, if anything, worse. “Ultimately the bond of all companionship,” he once observed, “is conversation.”

In a letter to the Home Secretary, begging for mitigation of his sentence, the poet and playwright refers to “this silence, this solitude, this isolation from all human and humane influences, this tomb for those who are not yet dead”. He pleads that he is on the brink of madness. Ironically, his eloquence defeated his argument. It was taken as proof of his sanity.

Again and again, Wilde’s letters from prison return to this theme of silence and solitude. In “The Ballad of Reading Gaol”, the long poem he wrote after his release, he recreates the mind-numbing noiselessness of exercise hour: “Silently we went round and round/ The slippery asphalte yard;/ Silently we went round and round,/ And no man spoke a word.”

In his heyday, he had habitually dined at the Savoy on clear turtle-soup, tender ortolans and Dagonet 1880. His prison diet was gruel and dry bread. The quality of the food gave him diarrhoea. To preserve their isolation, prisoners defecated into a small tin pot in their cells. Three times, warders entering Wilde’s cell in the morning threw up at the sight and smell.

The writer was so weakened by illness that once, during chapel, he fainted and fell, striking the side of his head. This caused an ear infection that would plague him until his death.

As I learned from Helen L. Johnston, Professor of Criminology at Hull University, Wilde’s hard labour would have been divided into first-class and second-class labour. The point of first-class labour was that there was no point. It was six to 10 hours a day at the crank or the treadmill.

The crank was a stiffly rotating handle attached to nothing. The warder could manipulate a screw to make the turning of the crank more difficult, which is why, some say, warders are known as “screws”. The treadmill, meanwhile, forced prisoners, like hamsters, to walk incessantly. In six hours, you might climb twice the height of Mt Snowdon. Unlike first-class, second-class labour had a purpose, such as sewing mail bags or “picking oakum” (unravelling rope fibres). On a rare visit, a friend noticed Wilde’s broken and bleeding fingernails.

The writer cannot have been the easiest of prisoners. After a month in Pentonville, he was transferred to Wandsworth, at which point he discovered that a certain waistcoat of his had apparently been misplaced. He screamed abuse at the warder, before recovering and apologising: “Pray pardon this ebullition of feeling.”

Late in 1895, thanks to an influential friend, he was again transferred, this time to the slightly more lenient Reading Gaol. En route, he suffered his lowest point. He was spotted on the platform at Clapham Junction by strangers, who jeered and spat at him. “For a year after that was done to me,” he wrote, “I wept every day at the same hour and for the same space of time.”

On reaching Reading, he learned that his once long and luxurious hair was going to have to be cut. “Must it be cut?” he complained to the warder. “You don’t know what it means to me.”

Amid his misery, small acts of kindness had a disproportionate effect. Once, while walking in the yard, he heard a fellow prisoner murmur, “Oscar Wilde, I pity you because you must be suffering more than we are.” To which, without turning his head, Wilde cautiously replied, “No, my friend, we are all suffering equally.” Yet his heart filled with hope and gratitude.

Soon afterwards, Wilde learned which prisoner it had been, and was caught speaking to him during chapel. Hauled before the governor, Henry Isaacson, both men were asked which of them had spoken first. Both claimed to have done so, and both were punished, being confined to the so-called dark cells in the basement for two weeks of prolonged sensory deprivation.

When I visited HM Prison Reading on a Tuesday afternoon, it proved a haunting experience. The cell bells, which prisoners later used to attract warders, were on the blink, so that every few seconds, a shrill tone would sound. It was as if the ghost of some long-dead lag was demanding attention. Yet when I descended to the dark cells and asked to be locked in, those bells were shut out. The bolt clanged home. That was it. The darkness was total. Each cell is entered through two doors. This was to prevent light getting in, when food was passed through the inner door.

As the architecture critic Jonathan Morrison told me, Reading Gaol, with its many cells measuring 7ft by 13ft, will be a tough structure to transform into an arts centre. Yet it should repay the effort, since the man who designed it, George Gilbert Scott, was “one of the greatest Victorian architects and gets as close as anyone has to elevating the penitentiary above the base needs of its gaolers”. Scott built it in red brick in the shape of a mighty cross. The governor himself lurked at the intersection, from where he could see the doors of every prison cell.

Forbidden to speak, Wilde was denied writing materials for his first year, except for the odd letter. He read the few books in the library so often that they became “meaningless” to him. Thanks to RB Haldane, the same friend who had got him transferred to Reading, he received some extra volumes, including books by Walter Pater, Cardinal Newman and St Augustine.

Yet Isaacson was a strict governor, who was determined to “knock the nonsense out of Wilde”, as he put it. He confiscated those books as punishment for minor infractions, and Wilde, who found it hard to resist talking, committed them frequently. For his own part, he described the governor as having “the eyes of a ferret, the body of an ape, and the soul of a rat”.

On 7 July 1896, a certain Charles Thomas Wooldridge was hanged within the walls of the prison. He was a 30-year-old trooper, who had cut his girlfriend’s throat with a razor.

In “The Ballad of Reading Gaol”, which Wilde dedicated to “CTW”, he reflected that “each man kills the thing he loves”. In his case, this couldn’t have been more true. He and his lover, Alfred Douglas, destroyed one another. Wilde ruined the life of his wife and two sons. He never saw her, or them, again. What arguably he loved almost as much was applause. On Valentine’s Day 1895, The Importance of Being Earnest, a silly, brilliant play of stunning perfection, and Wilde’s greatest success, had enjoyed its first night. Just three months later, the author was in the dock.

To Wilde’s relief, a fortnight after Wooldridge’s execution, governor Isaacson was replaced by a softer-hearted man named James Nelson, who told him, “The Home Office has allowed you some books. Perhaps you would like to read this one. I have just been reading it myself.” Wilde broke down in tears. He would later describe Nelson as “the most Christlike man I ever met”.

The remaining 10 months of his sentence proved significantly less vile. As his fame spread through the prison, warders even started to come to him for his literary opinions. Was Charles Dickens any good, one of them asked. Yes, Wilde replied, Dickens was a great writer. What about the popular novelist Marie Corelli, another wanted to know. On the contrary, came the reply, the author of Vendetta! and The Sorrows of Satan wrote so badly that she deserved to be locked up with the rest of them in Reading Gaol.

At first, when Wilde himself put pen to paper, whatever he wrote was taken away at the end of the day. This made sustained composition impossible. Its effect was the same as that of the Separate System on friendship. If you couldn’t recognise a fellow prisoner behind his cap, you couldn’t build a relationship. If you couldn’t read what you had written, you couldn’t add to it.

From January to March 1897, Nelson bent the rules to allow Wilde to compose a 50,000-word letter to Alfred Douglas, which would later be published under the title De Profundis. It is petty, petulant, vengeful, sometimes absurd, but also in many places beautifully written and profoundly touching. It was an act of grace to allow the author this emotional vent at that time.

In the last seven weeks of his sentence, Wilde took comfort in the kindness of a newly appointed warder. Thomas Martin, an Irishman, smuggled in copies of the Daily Chronicle and Ginger Nut biscuits for him. The pair developed a nagging, bantering friendship. Once, Wilde wrote Martin a note in which he declared himself happier because he now had “a good friend” who “promises me ginger biscuits”. At the bottom, Martin scribbled a reply: “Your ungrateful I done more than promise.” He was later sacked for giving biscuits to a child.

Wilde was extremely unlucky to miss out on the reforms of the 1898 Prison Act, which was passed in the year after his release. The Separate System remained in place until 1931, but treadmills were abolished and the possibility of a reduced sentence for good behaviour was introduced. The new approach was founded on the principle that something good might come out of bad – the same principle that is the basis of the campaign to turn the prison into an arts centre.

Game of Thrones actress Natalie Dormer, who grew up in Reading, wrote to me to add her voice to the cause. “In a time of post-lockdown, crippling costs of living and great pain and uncertainty in the world, artists and communities coming together to explore compassionately what it is to be human through theatre, yes, but also through exhibition, talks, and music, is the greatest reassurance that could be given. We need more unifying community arts spaces and Reading Gaol is a perfect candidate. I am reasonably certain Mr Wilde would agree.”

It seems a safe bet. Wilde struggled to write anything substantial after his release. In the event, his only major work was “The Ballad of Reading Gaol”. After two years of silence, he was readier to talk than to write. He died in 1900 from the ear infection stemming from his injury in prison. Yet he was always touched by the spectacle of beauty in unexpected places.

On May 18 1897, he was being moved back to Pentonville before his final release the following morning. There was some concern that he might be recognised en route, as he had been at Clapham Junction. Yet he couldn’t restrain himself. From the platform at Twyford he spotted a flowering bush, threw wide his arms, and exclaimed, “Oh beautiful world! Oh beautiful world!”

To this, the sober warder remarked, “Now, Mr Wilde, you mustn’t give yourself away like that. You’re the only man in England who would talk like that in a railway station.”

To support the campaign to turn Reading Gaol into an arts centre, go to savereadinggaol.uk