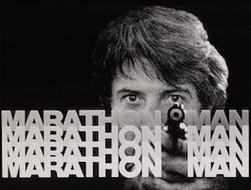

Dustin Hoffman staggered in, his face haggard, his hair rearing up like a herd of wild horses. “I’ve stayed awake three nights preparing for this role,” the actor confided to Laurence Olivier, his older co-star in John Schlesinger’s 1976 thriller Marathon Man. The latter patted Hoffman on the shoulder. “My dear boy,” he suggested gently, “Why don’t you try acting?”

This patrician dismissal has gone down as the classic sneer at the extremities of Method acting. It’s still the response of some to tales of Daniel Day-Lewis, say, staying in character during breaks in filming, or Leonardo DiCaprio eating a bleeding hunk of raw bison liver on the set of the 19th-century survival story The Revenant.

Yet the last laugh, arguably, is on the laughers. Hoffman and Day-Lewis have enough Oscar statuettes between them to open a sculpture park, and DiCaprio looks set to bag his first Academy Award.

So my question is this. If the Method works so well for actors, why hasn’t it been explored more by authors? The principle is the same, particularly for novelists, who must immerse themselves, like actors, in the sensations of being someone other than themselves.

I’m not just talking about research, although that’s a part of it. I also mean the deliberate use of theories created by the Russian actor and director Constantin Stanislavski and later developed at the Actors Studio in New York by the likes of Stella Adler and Lee Strasberg. Although there are differences in the teachings of these gurus, they all agree that the actor should believe, or practically believe, that he or she really is the part they’re playing, and that no recourse is too eccentric if it will assist this elevated mental state.

A bona fide Method writer, therefore, would display a similar commitment to his or her craft, both in degree and kind. Specifically, they would tailor the physical circumstances of writing to their subject matter. Last year’s Booker-winner, Marlon James, listened to Bob Marley’s Exodus album on repeat while penning his reggae novel A Brief History of Seven Killings. And Sebastian Faulks, I’ve learnt, pins up a photograph of a different “patron saint” for each of his novels and intermittently gazes at it, in hope of inspiration.

Yet you have to admit this is pretty thin gruel, by comparison with the antics of certain actors. Where, I wanted to know, was the Leonardo DiCaprio or Dustin Hoffman of novel writing? In my despair, I turned to my friends and acquaintances – and here I struck gold.

My first discovery was Thomas Fink, author of The Man’s Book, a slick guide to masculinity. His method for writing it, I learned, was immersive. Before penning his section on beards, he grew one. When it came to writing about wedding etiquette, he dressed himself in a morning suit. And for his chapter on hangovers, he dutifully embarked on a massive bender.

My second find was Alexander Fiske-Harrison. He trained as a matador in Spain as research for his book about bullfighting, Into the Arena. He is also an actor who, like Dustin Hoffman, has honed his technique at the Actors Studio. So for him, nothing was more natural, when he sat down to write, than to don the same black “country suit” and short jacket he’d worn in the arena. Between bursts of typing, he would move about the room, performing what is known as toreo de salon.

I hear the ghost of Olivier. “My dear boys! Why don’t you try writing?” Fair enough. But let me complete my trio of Method writers with one last example: myself.

My own novel was largely written in a cupboard. Memoirs of a Stalker is about a disturbed man who hides in his ex-girlfriend’s house for months on end and spies on her. Having studied Method acting myself, albeit briefly, I inevitably pondered the possibility of actually writing this story in one of my cupboards at home. What would be the downsides? I might, I realised, lose the respect of my wife. I decided it was worth the risk.

I must admit I encountered a few problems along the way. The cupboard I chose, a long low cavity above our marital bed, was hard to get into. So I bought a lightweight telescopic aluminium ladder. Lying on my back in the dark, I found my knees pressed against the roof, leaving insufficient room for a laptop. So I was forced to write on my mobile phone.

So does this approach improve the quality of the prose? The Man’s Book and Into the Arena have both been critical and commercial successes. As for Memoirs of a Stalker, I suggest you read it and decide for yourself. You can console yourself for the expense with the thought that you’re getting in at the start of a new literary movement, whose launch I proclaim now: the Method Writers. Fink, Fiske-Harrison and Hodgkinson. The flow of those names has a certain alliterative rightness, you’ll admit.