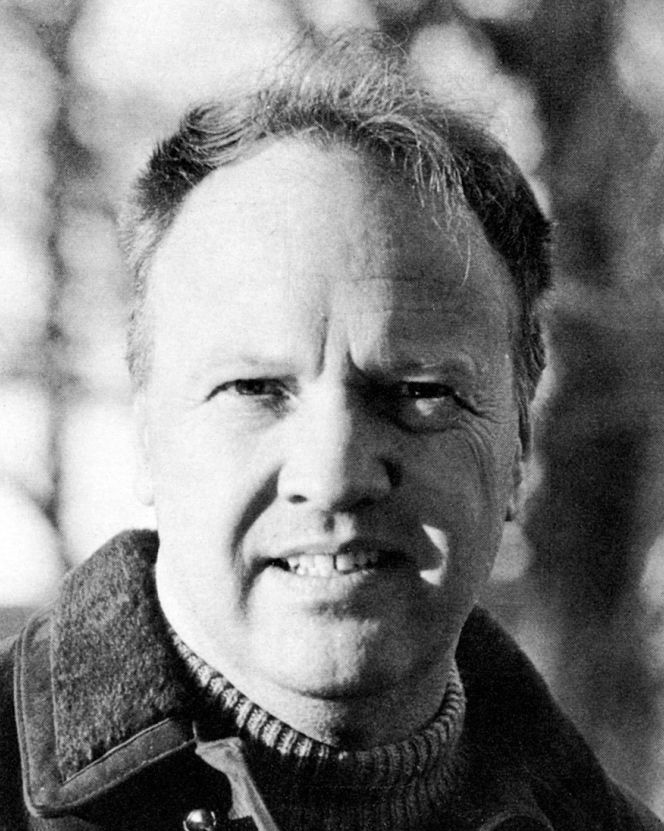

“It seems to me that I am the bearer of some kind of immortal message to humankind.” That was what the author James L. Dickey wrote in his diary during the filming of Deliverance.

A rangy, brawling poet from the American deep south, Dickey was drunk a lot of the time, so anything he said should be taken with a pinch of salt. Indeed, the story goes that he liked to to wander around muttering: “Oh, I’m so big! I’m so damned big!”

He was, at least, telling the truth—both literally (he was 6ft 3in) and metaphorically. Deliverance, which was based on the writer’s 1970 bestselling debut novel, really was big — despite or because of the scandal it provoked.

Released 50 years ago this month, it’s one of those films that, once seen, is hard to forget. Like Lord of the Flies, it reveals the horrors that human beings are capable of when their very survival is at stake.

Set in the southern state of Georgia, Deliverance tells the story of Lewis (played by Burt Reynolds) who takes his friends Ed (Jon Voight), Bobby (Ned Beatty) and Drew (Ronny Cox) on a canoe trip down a river before it is due to be flooded and its famous rapids destroyed by the creation of a hydroelectric dam.

From the start, there is an uneasy, unspoken tension between the visiting ‘city boys’ and the local ‘rednecks’. In one of the film’s iconic early scenes, Drew, with his guitar, challenges a boy with a banjo to a musical duel (the resulting Bluegrass number later spent 4 weeks at No2 in the Billboard chart). When Drew offers to shake hands, the boy does not respond.

The real horror starts when the group set off on their adventure. Some way downriver, Drew and Bobby are confronted by two locals, one carrying a shotgun. Bobby is made to undress and in a scene infamous in cinematic history, he is raped by one of the rednecks who demands that he ‘squeal like a pig’.

Lewis (Reynolds) bursts from the undergrowth and kills the rapist with a bow and arrow. The rapist’s companion escapes and the four friends decide to bury the body and continue on their way—but it looks as if the surviving redneck is in pursuit, determined to exact revenge.

The violence portrayed in the film – and above all that lengthy scene of male rape – shocked cinema goers and critics alike. Rural folk in Georgia were outraged by their portrayal as ‘inbred sex offenders’.

For the celebrated American critic Roger Ebert, the film was exploitative sensationalism. “The appeal to latent sadism is so crudely made that the audience is embarrassed,” he pronounced.

Nevertheless, it made millions at the box office, was nominated for three Oscars in 1973 and is now seen as a classic: selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the US National Film Registry for being “culturally, historically or aesthetically significant’’.

Yet given the film’s turbulent production history, the real miracle is that it ever got made at all.

James Dickey, determined to retain control and convinced he was helping, repeatedly interfered. “I have a good director, though an Englishman,” he wrote warily to a friend.

The Englishman in question, John Boorman (Point Blank, Excalibur) chose to cut the first 19 pages of the screen adaptation Dickey had written on the grounds that it took too long for the river trip to begin.

Big Jim Dickey, drunk in his favourite watering hole, told anyone would listen: “God, they’re ruining my f***ing movie, ain’t they. They’re not doing my book.” Finally, in a rage, he attacked the director, who was seven inches shorter than him. He broke his nose and cracked four of his teeth.

Yet amazingly, it wasn’t this that persuaded Boorman to kick Dickey off the set. It was the way the author began bothering the actors.

According to actor Ronny Cox’s brilliant memoir, Duelling Banjos, Dickey took a particular liking to him after watching him shoot a scene.

Hammered on whisky in a bar, he bellowed at Cox, “Drew! Hey, Drew!” – he addressed all the actors by their character names as a mark of ownership – “Do that scene for us!”

Feeling self-conscious, Cox refused. When Boorman heard about this he banned the writer from the set. Dickey responded with an astonishing one-hour tirade, during which he took on the personality of each of the protagonists of his book in turn.

First he was the macho, posturing Lewis. Then he became Ed, the thoughtful one. Then he was Bobby the clown. He ended as the sensitive, poetic Drew. When he was done, he declared he was willing to leave, as long as each of the actors explicitly asked him to.

Reynolds, Voight and Beatty did so as diplomatically as they could. But when it came to Cox, he couldn’t: tears in his eyes, he said nothing.

Finally Dickey left in disgust and buttonholed Cox, saying: “Drew, I am so disappointed you didn’t have the guts to tell those guys that you needed me.” He didn’t realise Cox wanted him gone most of all.

Now director and actors were free to make the film. At first, Boorman had courted Marlon Brando and Jack Nicholson to play Lewis and Ed, but they had proved too expensive. Others considered were Robert Redford, Charlton Heston and Donald Sutherland (who rejected the script as too violent).

Boorman later made a virtue of using relative unknowns. Voight – the father of Angelina Jolie – had appeared in the hit film Midnight Cowboy with Dustin Hoffman, but Reynolds was known largely for TV work and had been spotted by Boorman on a chat show. “It’s the first time I haven’t had a script with Paul Newman’s and Robert Redford’s fingerprints all over it”, Reynolds joked later. “The producers actually came to me first.” The others were stage actors.

The advantage of having no big names, Boorman said, was that it was unclear to the audience which of them might die in the film.

And there were times on the shoot when all four did, literally, come close to death. The rapids of Georgia’s Chattooga river, where the film was shot, were dangerous, and the actors on what was a low-budget, uninsured production were obliged to do their own stunts.

One actor refused to get in his boat until he was shamed into it when Boorman led by example.

“It’s very simple!” the director declared. He grabbed an oar, Voight later recalled, jumped in the boat and set off. After that, the cast felt they simply had to brave the rapids.

Cox fell in and was rescued by a crew member just as he was about to disappear over a waterfall. Beatty sank to the bottom and said his last thought, before being pulled out, was: ‘I hope they find someone else to finish the scene’.

In another crucial scene, Voight has to climb a cliff to try to kill the murderous stalker. The actor lost his grip and nearly fell to his death.

Reynolds, who spends much of the film sporting a tight rubber vest designed to show off his biceps, was told before shooting a scene in which he goes over a waterfall that when the current sucked him down, he should go with it. Fight it, and he would be lost.

Reynolds did as told. He smashed into a rock and sustained a back injury that troubled him for the rest of his life. Moreover, after taking him down, the powerful current shot him up again so violently that his clothes were actually ripped from his body, leaving him stark naked.

“[The crew] didn’t tell me that it would shoot me like a submarine torpedo!” Reynolds later remembered. “They couldn’t find me for five minutes. Then, a mile down the river, they saw this nude man stumbling, crawling towards them. I’d had on these high boots and they were gone. The pants were gone. The underwear was gone. The jacket was gone.”

For the backward, back-woods characters in the film, Boorman cast from the local community. The boy banjo-player, played by Billy Redden, was discovered at a primary school. Billy McKinney, the actor who played the rapist, took a Method approach and intimidated his on-screen victim Beatty off-camera. At meals, he sat three tables away, just eyeballing him.

The result of this gritty realism and seat-of-the-pants filming is a movie that feels thrillingly realistic and bleak. But Deliverance is more than a gripping yarn of survival. At the time it was made, America was embroiled in the Vietnam War. The dissection of violence and machismo couldn’t help but be read in that context. The simple story triggered the same anxieties as Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness: it reinforced the message that we are all only a heartbeat away from reversing our evolutionary story and reverting to the brutality of animals.

And at a time when America is still picking through the political and cultural debris left by the riots at the Capitol in January 2021, this feels as relevant and resonant now as it was then.

Another reason why Deliverance feels of the moment, if you watch it today, is its environmental theme.

“They’re drowning the river, man,” Lewis drawls at the start of the film, referring to the building of the hydroelectric dam. “Just about the last wild, untamed, unpolluted, unfucked-up river in the South…They’re gonna rape this whole landscape.”

In the event, of course, it’s the interlopers from the city who get “raped”. It’s as if the river itself, served by the mountain men who live around it, is taking a pre-emptive revenge for the sacrilege it knows is going to be perpetrated upon it.

What begins as an action movie becomes a tense psychological thriller and ends as a horror film. And, as in other horror films, the punch resides in the fact that the thing that is conventionally thought of as benign – the mother, the child, the clown, or in this case, the river — is revealed to be the threat.

When big James Dickey eventually got to see the film, even he had to admit it was pretty good. He had been allowed back on the set to play a cameo as the sheriff who deals with the fall-out of the trip, after the surviving friends make it back to civilisation.

To show that there were no hard feelings, the author gave the main cast members a selection of gifts. Reynolds, Voight and Beatty received beautiful Bowie knives. To Drew, whom he felt had betrayed him, Dickey gave only a pocket knife. He couldn’t quite let go of the grudge.

The writer was hugely proud of the film when it was released: his son Christopher recalled how, stinking of alcohol, he staggered up and down the queues of people outside cinemas.

“You see that?” he would say. “That’s my movie.”

Deliverance is listed by Time magazine as one of the best novels of the 20th century. Dickey never wrote another as good.

An unexpected consequence of the film’s success was that city-dwellers came in droves to the backwoods of Georgia, often with little experience of white-water rafting, and took to canoes to try to recreate some of the feats performed in the movie.

Some died of hypothermia, others from having their heads bashed against rocks. Locals dubbed this “Deliverance Syndrome”.

The film put Cox and Beatty on the map as film actors. It confirmed Voight’s chameleonic ability to play a range of different roles. And for Burt Reynolds, it was simply transformative.

It set his macho image, while demonstrating that he was also an actor capable, in the right role, of considerable charisma. Later that year, he was crowned Cosmopolitan magazine’s first ever male nude centrefold, and he went on to become the world’s biggest movie star.

“It was crazy,” Reynolds recalled, thinking of the risks they took on set. “Absolutely crazy. But we did it and I’m glad we did it. Would I do it again? Not for three million dollars.”