There was once a little boy who dreamed of being a soldier.

His grandfather and great uncle had both been soldiers, killed at the Somme, their bodies never recovered. His father was a soldier, absent for most of his childhood. The little boy, whose name was Gerald Laing, did sketches of knights and paratroopers. At school, he drew arms and armour on his exercise books, as little boys will, fantastic escutcheons and scenes of elaborate gallantry. As soon as he was old enough, he joined the Army — and immediately realised that that wasn’t what he wanted to do with his life.

Laing wrote to his commanding officer in the Royal Northumberland Fusiliers, asking for permission to resign his commission. The letter was ignored, so he wrote to him again, and in due course he found himself hauled before his CO. “Laing,” he was told sternly, “if you continue writing letters of this sort, you will have no future in the Army!”

As it turned out, however, he was a stubborn romantic. It took years, but Laing broke the grip of the Fusiliers, enrolled as an art student at St Martin’s College, and became one of a bright new wave of British pop artists. His name is less well known today than some others — which is odd because, for me, his works have aged far better than the cluttered collages of Peter Blake, say, or formica pornography of Allen Jones. And if you don’t believe me, take yourself down to the Fine Art Society on New Bond Street, which from 19 September will mark the fifth anniversary of Laing’s death by hosting the first posthumous retrospective, comprising 70 of his best paintings and sculptures. You’ll see what I’m talking about.

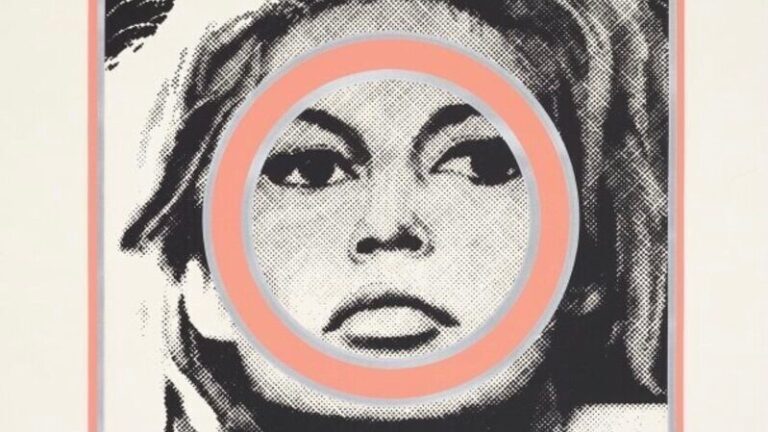

The early works that made his name — particularly the seductive portraits of the sullen Bridget Bardot and silken Anna Karina — seemed to be about celebrity. Which is one reason they still feel a propos. But as you take in the others, his stirring, stock, block-colour images of girls in bikinis, hot rod racers, free-fallers and astronauts, you realise the Arthurian quest of Laing’s life wasn’t for fame but perfection. That was what lured him to cross the Atlantic and throw himself into the New York scene: the present-tense perfection that seemed implicit in the American dream, the promise of Technicolour prosperity that struck such a contrast with the grey-greasy drabness of the Britain he left behind.

There can’t be many great artists who have also been commissioned officers. And at a glance, there seems a gulf between Laing’s military background and artistic bent. Then you realise his speed freaks and fall guys, like soldiers, risk their lives for a kind of cause, paradoxically making life more precious by valuing it less. Their “right stuff” is old, even mythic.

“The astronauts were the new knights,” Laing’s son Farquhar told me. “Their coat of arms was the Nasa logo. These were the brave. These were the fearless warriors of their time.”

And if that all sounds a bit noble, it must be admitted that Laing succumbed to some of the temptations of the high life. He was good-looking, a foot-down drinker and late-night addict, an accepter of invitations, who sometimes dressed garishly, as Englishmen only do abroad. “Where d’ya get that outfit? Wardrobe?” the film director Billy Wilder drawled, eyeing Laing’s Berkhamsted School old-boy blazer (black with gold and maroon stripes). Thanks to the patronage of his hip gallerist, Richard Feigen, he hobnobbed with the stars.

On one occasion, he went on a date with the starlet Mia Farrow, only to be refused entrance to LA’s Whisky A Go Go club on the grounds that she was underage. Another time, Feigen took him to meet Tony Curtis. The actor dragged a picture of himself out of a cupboard and said, “Richard, what’s this? Some artist sent it to me.” It was an Andy Warhol screen print.

Meanwhile, Laing was growing uneasy with fame. He understood instinctively the flip-sides of the cool 1960s ideal: the happy hedonism and its human cost. Yet Feigen didn’t want him diverging from his beach girls and extreme sportsmen, which had become part of the visual vocabulary of the time. He dismissed his political works such as Souvenir and Lincoln Convertible (responses to the Cuban Missile Crisis and killing of JFK). Laing, though, couldn’t keep still. Having achieved all he ever wanted, he realised it wasn’t what he wanted.

At the end of the decade, he returned to the UK and bought a small tumble-down castle in the Scottish highlands, which he set about renovating: a kind of Camelot for two. He had found his Guinevere in the feline form of his second wife, a preternaturally beautiful New Yorker named Galina. But he needed a new artistic direction to accompany his new life.

It eluded him for a few years, until, one night after a party in London, he found himself sharing a taxi at 3am, heavily drunk, with a man who was being boring. In his desperation to escape, Laing jumped out of the cab, barely knowing where he was. As it turned out, the driver had pulled up beside the steps of Charles Sargeant Jagger’s Royal Artillery Memorial at Hyde Park Corner, a butch slab of concrete guarded by trench-caped squaddies. As the black-bronze soldiers glared down at him out of the small-hours gloom, it was as if Laing was staring into the faces of his dead grandfather and great uncle. He caught a glimpse of an artistic truth, which would dictate the course of his career for years to come.

The former pop-art star became a public sculptor. And in the first instance, he suffered a catastrophic collapse in demand. Inevitably this rankled. In later life, Laing would quote the poet Paul Valéry, who remarked that “Tout se change, sauf l’avant-garde.” If you want to remain a fixture in the cutting-edge art market, you have to keep doing what you do.

That was never Laing’s style. After a gruelling campaign he won a new level of recognition. His towering Sherlock Holmes memorial stands outside Arthur Conan Doyle’s birthplace in Edinburgh. The dragons on his bronze bas relief at Bank Tube Station might have crawled from the pages of Mallory. In a sense, though, you could say that the deeper lesson of that night at Hyde Park Corner didn’t really become clear until 30 years later, when the world was shocked by images of the abuse of prisoners by American soldiers at Abu Ghraib in Iraq.

Laing already felt “incredibly passionate” about the Iraq War, according to Farquhar. As a former Fusilier who had served in Northern Ireland, “he knew all about going into people’s houses and turning everybody out of their beds in the middle of the night”. In his disgust, he reached for the pop-art idiom that he had perfected in the 1960s and used it to create his scorching Abu Ghraib series. Unlike his earlier works, these achieve their power from the risky mismatch of form and content: a cheerful, magazine-cover take on sickening cruelty. Critics didn’t go for the pictures at first and Laing struggled to get them shown in London. Two have since been bought by the National Army Museum. It’s time for a reappraisal.

Far from exploiting the suffering on show, his Abu Ghraib pictures help to ensure that it won’t be forgotten. They are, if you like, Laing’s equivalent of the Jagger memorial.

He had had to move away from the pop style for decades in order to return to it with a new virtuosity. Portraits followed of a new breed of celebrities, which also equal or outpace their earlier counterparts. There’s a vision of Kate Moss that is part-Picasso, part-Testino. Or consider his Loony Tunes image of a clinch between the doomed singer Amy Winehouse and her black-suited boyfriend Blake Fielder-Civil. With typical bravado, Laing dubbed it The Kiss, convincingly laying claim to a tradition roping it in with works by Klimt and Rodin. But it’s the anti-war images you will keep going back to. For Laing, art had first represented an escape from war. Yet war was the theme that haunted him, at first implicitly and later explicitly. Farquhar, who sees his father as the most talented British artist of his generation, hopes the Fine Art Society show will tie his work together, presenting a “career that flows”. That’s what it does. It’s a dazzling tribute to a man who, from a boy who drew knights on his schoolbooks, grew up to be one of the great anti-war painters of his time.