“Over the points by electrical traction, out of the chimney pots into the openness, till we come to the suburb that’s thought to be commonplace, home of the gnome and the average citizen.” Fifty years ago, the BBC documentary Metro-Land aired for the first time. These free-flowing dactyls, which mimic the motion of a train, were delivered over the footage by the newly appointed Poet Laureate, John Betjeman, as he rode the Metropolitan line out into the middle-class Arcadia of Middlesex. They don’t write voiceovers like that anymore.

Hailed as a masterwork right off the buffers, Metro-Land was a hymn not only to Betjeman’s suburbia but also to the Tube that took him there. For the poet, it turns out, was a lifelong lover of trains, Underground or otherwise. He played with models of them as a child. In his teens, with a like-minded friend, he set himself the challenge of visiting all 200 or so Tube stations, as he recalled in his verse autobiography:

Great was our joy, Ronald Hughes Wright’s and mine,

To travel by the Underground all day…

Young Ronald grew up to become a Catholic priest. Young John never grew up. As with a lot of artists, his direct line to his childhood was a distinguishing feature. Yet he went on to establish himself as, among other things, the benign Orpheus of the Underground. His feeling for it overflowed in his poem Middlesex, which begins,

Gaily into Ruislip Gardens

Runs the red electric train.

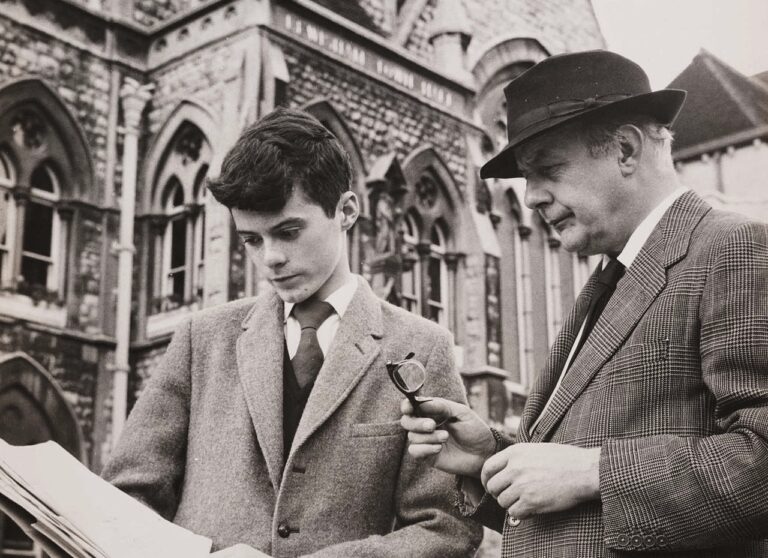

It reared up more than once in another Betjeman documentary, A Poet in London (1959), in which the poet gloomily wanders the platforms at Aldersgate Street station (now renamed Barbican) and laments in verse the recent removal of its majestic glass-and-steel roof.

The entire movement of poetry in the 20th century was towards finding beauty in unexpected places. In this respect, Betjeman was far more modern than is generally supposed. I find myself thinking of him as, on my morning commute, I push forward with my current novel, which is about a man who lives full-time on a Tube train. Having always loathed the Underground, my hero comes to appreciate the chunky arterial red-and-orange wiring on the walls at Baker Street; the bunched yellow poles of the Circle line; the tension of proximity and strangeness in the rush hour crush; the unending variety of other people; and the ceaseless rhythm of trains, which another former Poet Laureate, Carol Ann Duffy, described as “soft Latin chanting”.

Betjeman may have been the greatest, but he isn’t the only poet to have written about the Tube. One of the earliest was a 14-year-old named Edwin Parrington, who in 1908 won a competition to come up with a slogan to promote the network. His entry ran:

Underground to anywhere,

Quickest way, cheapest fare.

A hundred years later, the rock band Yeti contradicted his claim in their song Northern Line:

Just quit. The train ain’t never getting anywhere.

There’s a signal failure at Leicester Square.

In 2013, John Hegley marked the 150th anniversary of the creation of the London Underground with a terrific tribute, which concludes:

Here’s to the gaps, the maps

And the elapse of a hundred and fifty years since that first

Steaming monster hurled

Through its Metropolitan Minotaur world.

To all the billiard ball-bottomed straps onto which I’ve hung.

And here’s to the police officer, who when I was illegally busking outside Westminster Station, approached me and said,

‘Do you know any Neil Young?’

Anyone now looking for a monument to Betjeman can find it in his poetry, and in the bronze statue of the poet that stands within the intricate Victorian edifice of St Pancras Station, which he fought in the 1960s to preserve. Beneath his scruffy, ingenuous figure, the plaque reads, “John Betjeman, 1906-1984, poet, who saved this glorious station.”

When he died, there was a memorial service at Westminster Abbey. The Prince of Wales read Ecclesiasticus 44, 1-15 (“Let us now praise famous men…”). The actress Prunella Scales recited Betjeman’s poem South London Sketch, 1844. For our theme, though, the most fitting tribute came from the Abbey’s Precentor, the Rev Alan Luff, who said:

Let us give thanks for the fulness of John Betjeman’s earthly pilgrimage and for the way he enriched the life of us all. For his skill and sincerity as a broadcaster. For his opening of our eyes to see the beauty in things condemned by fashion. For his courage in leading the fight to preserve the things he found valuable. For his delight in trains and railways and the Underground.