Let’s hear it for obscurity. Put your hands together for the empty stage. It’s time to celebrate the “anti-celebrities”: brilliant people who, owing to their distaste for or lack of interest in fame, didn’t receive due recognition in life. Which is the way they wanted it.

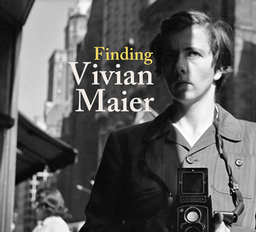

Out now in cinemas, the documentary Finding Vivian Maier tells the story of a nanny who just happened to be one of the great photographers of the 20th century. No one knew that until after her death, because she didn’t bother to develop most of the pictures she took while wandering the streets of Chicago, let alone send them to art galleries. The film, which takes much of its power from her haunting images, presents this as an enigma: why, it asks, did Maier shrink from fame?

Its answer, at least in part, is that she was as mad as a sparrow. This was a woman whose first request at a new job was that her employer fit a bolt to her door; who slammed a five-year-old girl into a bookcase for struggling to tie her shoelaces; and who — in clinical proof of mental instability — collected newspapers. She was clearly a little eccentric. But I’d like to suggest an additional explanation, one that is humbler, simpler and, I think, more generous to Vivian Maier. She didn’t want the fuss.

As an obituary writer, and by extension reader, I’ve found myself in an ideal position over the past few years for the gentle sport of anti-celebrity spotting. In most cases, you see, the degree of talent is such that it earns the individual a discreet or decent notice in the obituary pages, even if they strove, in life, to avoid attracting too much attention.

The patron saint of anti-celebrities was J.J. Cale. The Oklahoma-born singer-songwriter, who died last year, is the focus this month of The Breeze, a tribute album compiled by Eric Clapton. Clapton hero-worships Cale, once naming him his “all-time favourite person”. Mark Knopfler, Neil Young, Johnny Cash: the catalogue of Cale’s fans is a rock’n’roll hall of fame. So how is it that the fame of a Clapton or Cash evaded Cale during his long and languidly brilliant career?

Put simply, it seems he was evading it. Glance at the artwork of Cale’s albums and you’ll see something strange: he isn’t there. It wasn’t until the eighth — named, with characteristic concision, #8 — that he was so presumptuous as to put an image of himself on the sleeve. “I always wanted to be part of the show,” he said once. “I never wanted to be the show.”

Most anti-celebrities reach an anti-Rubicon moment: when, with one step more, their lives could have been transformed out of recognition. So it was with Cale, who in 1971 was invited to perform his song Crazy Mama on American Bandstand, which commanded an audience of millions. He refused after learning he’d have to lip-sync to the lyrics: to sync, that is, rather than sing. “I’m a musician,” he explained. “I’m not an actor.” The result? The song sank after peaking at No 22 — which, as it turned out, was the biggest hit of his career.

My point, though, is that Cale didn’t flinch or blanch. He shrugged. He took a step back. And the argument I want to make is that for this he deserves the praise he never pursued.

Not having much experience of fame myself (my efforts to avoid it have so far proved phenomenally successful), I consulted an expert. Dr Glenn Wilson, the author of Fame: The Psychology of Stardom, told me that the process of celebrity tends to involve “spending the first 10 years trying to get noticed, and the second phase is wearing dark glasses and hiding round corners, in order to avoid getting noticed”.

There are, of course, anti-celebrities whose penchant for sabotaging their own careers was part of a pattern of self-destructiveness that cannot be envied. Take Nicol Williamson. A man Laurence Olivier named his nearest rival for the title of Britain’s greatest actor, the russet-haired Scotsman was hailed as the Hamlet of his generation. The diminishing echoes of applause reached Richard Nixon, who invited him to the White House to put on a one-man show. Instead of appearing with sword and skull, as Nixon had hoped, Williamson slouched in, wearing jeans and T-shirt, and proceeded to intersperse his Shakespearean monologues with country songs.

In a tale recounted in Plato’s Republic, the Greek hero Odysseus is given the chance in the Underworld to decide what kind of person he wants to be in the next life. A king? A warrior? A great poet? No, he chooses to be an ordinary citizen, a regular guy, described in the Greek as apragmon, which literally means “free from business”, though there’s no very good equivalent for it in English. (I’ve always assumed James Joyce had this story in mind when he invested his ordinary citizen, Leopold Bloom, with the soul of Odysseus in Ulysses.)

You might suppose that the true anti-celebrity — the pure “apragmonite” — would pick a profession less invested with performance anxiety than music or film or the theatre. He might become a journalist, like Anthony Lawrence, who served 17 years as the BBC’s man in the Far East.

Lawrence’s Vietnam dispatches were so quietly perfect, they are still cited as models of the form. Yet he repeatedly turned down transfers to more glamorous postings, and after retiring stayed on in Hong Kong with his German wife (whom he referred to affectionately as “the enemy”, having fallen for her in postwar Berlin). At his 101st birthday, he exhorted guests to “Drink up and be happy. Because after all, that’s the main point.”

Another who sees “the main point” is the American singer-songwriter Sixto Rodriguez: a performer, but a classic anti-celebrity. The subject of the 2012 documentary Searching for Sugar Man, Rodriguez tipped into obscurity in the 1970s after releasing two tender, heart-rending albums. He later became a star in South Africa, but was never told, because of an inconvenient rumour that he was dead. Some said he had set fire to himself on stage; others that he’d blown his brains out.

The best thing about the documentary is the mild geniality with which Rodriguez responds, on learning that, in Cape Town, he’s bigger than Elvis. When Searching for Sugar Man was up for an Oscar, he declined to attend the ceremony, on the grounds that he didn’t want to distract from the achievement of the film makers.

Don’t you just love these shiftless paragons? More, at any rate, than their giftless opposites: celebrities whose celebrity is their single commodity. Let’s not name names, since they get named often enough as it is. But that’s my drift. The ones to name are the anti-celebrities. Why? Because they wouldn’t much mind whether you named them or not.

So go on: gaze at Maier’s spectral photographs. Listen to the bluesy grooves of Cale and the bruised ballads of Rodriguez. Read Lawrence’s cool dispatches and seek out Williamson’s coruscating performances. And while you’re at it, drink up and be happy.