It should have been a triumph of European cooperation. A hundred and fifty years ago this month, four English travellers and three continental guides (a Frenchman and two Swiss) set off from the little village of Zermatt in the Swiss Alps to try to become the first men to climb the Platonically perfect-looking mountain called the Matterhorn. All seven succeeded, but only three survived.

The lessons of what happened that day still resonate beyond the sphere of mountaineering. At the risk of stretching the analogy with other European projects, the first is that if a group is bound together, and not tied to a fixed external point, it may only be as strong as its weakest member. On the slopes of the Matterhorn, that was an inexperienced 19-year-old named Douglas Hadow.

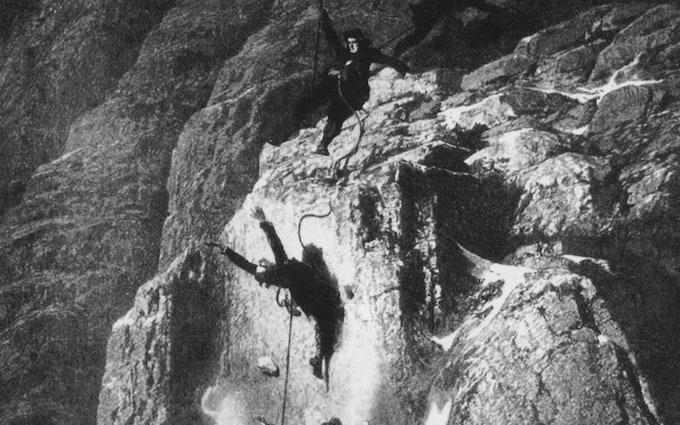

At the steepest part of the descent, all seven were roped together. None of the survivors saw what happened, but it’s supposed that Hadow slipped, pulling the three nearest to him off their feet. Since no one had hammered a piton into the rock, they all might have died. But climbers four and five were connected by a thinner length of rope. On taking the strain, it snapped.

Young Hadow; a sturdy vicar named Charles Hudson; Michel Croz, a pipe-smoking French guide; and Lord Francis Douglas, the amiable 18-year-old brother of the mad Marquess of Queensberry. These four slid out of sight with hardly a cry, although Croz is said to have shouted, “Impossible!” as he vanished over the edge. They then plunged some 4,000 feet to the glacier below.

A few days later, a media storm broke across Europe, a swirl of newsprint, a blizzard of blame and pontification. It was fiercest in England, where The Times devoted no fewer than three leading articles to the matter. In one of them, it described Lord Francis as “one of the best young fellows in Europe”. In another, it questioned the point and purpose of this crazy new pastime of mountain-climbing. “Is it life?” the leader demanded, the first in a rockfall of rhetorical questions. “Is it duty? Is it common sense? Is it allowable? Is it not wrong?”

Was it allowable? Queen Victoria wasn’t sure. Endearingly, she asked her prime minister, William Gladstone, if mountaineering might be made illegal for Englishmen. His response isn’t recorded.

Was it duty? Charles Dickens didn’t think so. The novelist argued that the climbing fad was as whimsical as if someone vowed to mount “all the cathedral spires in the United Kingdom”.

Was it common sense? We know what Dickens, The Queen and The Times would probably have said. Yet the better question, arguably, is not whether the desire to climb the mountain was sensible (of course it wasn’t), but how it might more sensibly have been done. If you visit Zermatt – where, this month, countless commemorative events, performances and walking tours are being held to mark the anniversary – step into the Matterhorn Museum, and seek out the broken rope. Its slimness takes the breath away. It’s about as thick as a breadstick, and looks as easy to break.

As with most major balls-ups, the Matterhorn disaster wasn’t the fault of one person. It was caused by a series of bad decisions, and decisions not taken, for which the blame was shared.

The worst of these was the failure to designate a leader. Pure democracy, requiring a universal vote on any important question, is unworkable. In practice, a leader must be elected who has the power, over a set period, to push decisions through. In the case of the Matterhorn expedition, this didn’t happen, probably because it wasn’t obvious who that leader should be.

Lord Francis was an aristocrat, set for a military career, who had proved himself an able climber. At 36, Hudson was the oldest, a very good climber, a man of the cloth. And then there was Edward Whymper, a 25-year-old engraver (not from the top drawer socially) who was travelling the Alps sketching the peaks for an English publisher. He was probably the most gifted climber.

Any of these would have done. Any of these might have taken the decision, for the good of the group, to exclude the weakest member, the one whose knees were starting to shake.

The aura of a curse shadowed the enterprise. According to local superstition, there was a derelict city on the Matterhorn. It was said to be home to “gins and effreets”, to use the words of Whymper. Swiss folklore warned of “barbegazi”: hairy homunculi with enormous feet, which enabled them to surf on avalanches (the name comes from barbe glacée, meaning frozen beard).

Needless to say, no such goblins were encountered, nor any ruined palaces. The summit was silent and empty, and in a burst of schoolboyish spirits, Croz and Whymper sprinted for the top. It was sportingly agreed that they had reached it at exactly the same time. On one side, lay the grey peaks of Switzerland; on the other, the red hills of Italy. It was 2pm on 14 July 1865.

There’s a nightmarish quality, in retrospect, to the activities of the seven on the summit, as they faffed in the cold sunshine. Pipes were smoked. Croz hung a shirt as a flag. Whymper sketched.

Some chat was held as to whether it might be a good idea to use a fixed rope at the steepest part of the descent. For it was here, coming up, that Hadow had found himself struggling. He was strong, of athletic stock (his brother Frank would win the second ever men’s tennis title at Wimbledon, and is credited with inventing the lob). But once you get the jitters, they’re hard to shift.

The others had had no such trouble. In fact, they had found the climb a cinch. For it turned out that the east face of the Matterhorn – which looks pretty forbidding today to the speculative skier, goggling from his chairlift – was less steep than it had always appeared: more of a scramble than a climb, except at that steepest part, which was where it all went wrong.

Hudson and Whymper had settled that a rope should be fixed. But after they began the descent, the latter realised that he had neglected the tradition of leaving their names in a bottle. He hastened back up in order to attend to this trivial chore. By the time he rejoined them, the others had reached the steep bit. Neither Hudson, nor anyone else, had fixed a rope to a piton.

He tied in between the two Swiss guides, a father and a son who, both being called Peter Taugwalder, were known as Young Peter and Old Peter.

Then came the slip. Croz’s cry. The sound of falling rocks, and more than rocks. Old Peter tried to brace and the thin rope broke.

A few seconds later, Whymper and the Taugwalders found themselves alone on the hillside.

The Englishman later accused the Swiss of going to pieces. They, meanwhile, said the same of him. According to Whymper, Old Peter burst into tears, while Young Peter wailed, “We are lost! We are lost!” Against this, Young Peter would recall that, when they eventually moved off again, Whymper was “trembling and could scarcely take another safe step”. In Whymper’s account, the Swiss informed him that they had decided to refuse payment for their services. This, they confessed, was so people would pity them, meaning they would receive more cash in the long run.

Outraged to find them thinking of money at such a time, he lost his temper, and the mood grew ugly. Since it was too late to reach Zermatt in daylight, the three pitched camp, and Whymper, exhausted and paranoid, began to think how convenient it would be for the Taugwalders if he too met with an accident. He passed a sleepless night, on his feet, his ice-axe gripped in his hands.

Whymper never blamed Old Peter for not tying on to Lord Francis with a thicker rope. He must have known that the rope that broke had probably saved his life. In those days, the use of such thin ropes wasn’t so unusual. It was only afterwards that experiments were carried out to determine the weights different ropes could bear, the results absorbed by the climbing community.

Several days passed before a team of English and locals, including the resilient Whymper, succeeded in reaching the bodies. They lay in the snow, half-naked and horribly mangled. Hadow was identified by some hanks of hair; Hudson by a letter to his wife Emily, and by his crucifix, which had buried itself in his chin. The worst to see was Croz, who had lost the upper part of his head.

“He was simply smashed,” Whymper noted. “As if some tremendous giant had taken him and had dashed him against rocks over and over again, until all semblance of humanity was obliterated.”

There was one body missing, that of Lord Francis. They found his boots. His brother (who would later persecute Oscar Wilde) hurried to Zermatt and roamed the hills in search of him, to no avail. His sister Florence instituted a reward for his recovery. It was never claimed. He seemed to have been vaporised on the way down, reduced to a red mist, which had floated away on the breeze.

It was hard not to attribute a personality to such violence, as if the Matterhorn itself had exacted a kind of revenge. Or it was Nature, flexing her muscles. And what of the detail of the crucifix that had stabbed the vicar’s chin? Surely this was proof, if proof were needed, of the non-existence of god. The rosary beads belonging to the Catholic Croz had been “pulverised”.

Hudson’s widow wrote to Whymper, alluding to this disturbing implication even as she denied it: “The blow has been a terrible one to me, but it has not shaken my belief in God’s overruling providence. I believe that it has been for some wise and good purpose of his own that he has permitted this sad calamity to happen, and I trust good may come out of it to all concerned.”

But it was vain to try to find meaning in an event, whose meaning lay in the lack of it. The error of one member of the group had brought disaster on all, not only the ones who died. Whymper never shook off the association, and ever afterwards climbed alone, for fear of another such mishap. Old Peter, who felt he was blamed for the tragedy, suffered a breakdown. Only Young Peter, and the village of Zermatt, benefitted. As a professional guide, the former climbed the mountain on countless subsequent occasions. The latter became one of the best-known resorts in the Alps.

The first question that was posed by The Times in its anguished editorial was: “Is it life?” The last was: “Is it not wrong?”

What most shocked about the Matterhorn tragedy was its lightness: how casually the summit had been reached, and how carelessly disaster had struck. It wasn’t wrong. But it was life.