If you find yourself at the foot of London’s Park Lane with five minutes spare, try dashing into the traffic. This rash act is the only way to access a little roundabout, which conceals one of the dirty secrets of British art history. By vaulting the crash barriers, then ducking under the canopy of spiky plane tree leaves, you’ll come upon a partially concealed statue of Lord Byron. It is not a very good statue but it’s the plaque underneath that is the point of interest. It is attributed to a now-forgotten sculptor named RC Belt.

At the time it was unveiled, there were some who whispered that the Byron sculpture wasn’t actually by Belt at all. Then in 1882, it, along with other works attributed to Belt, became the centre of the longest libel trial in British legal history. Stretching over half a year, the case of Belt v. Lawes, in which Richard Claude Belt sued his rival sculptor Charles Bennet Lawes for calling him a talentless impostor, was the talk of the town.

It was also a circus. As evidence, Belt crammed the courtroom at Westminster Hall with over 30 of his statues and busts, including a life-size nude of the 5th century Egyptian mathematician Hypatia in a startlingly ecstatic pose. The sculpture now stands in an alcove of the Livery Hall. It’s quite a sight. The archivist, Penelope Fussell, told me that during the trial this statue had caused a stir because it was clear to onlookers that the physical inspiration had come partly from Belt’s fiancee, and partly from his mistress, both of whom were present.

How had this come about? It seems that Belt — who died 100 years ago today, his reputation in tatters — was the victim of his own success, combined with a pinch of hubris, and a heavy side-order of class prejudice. Born into poverty in East London, he worked for four years at the studio of a sculptor from an altogether different background. Fiercely competitive, an athlete as well as an artist, Charles Lawes was the old Etonian heir to a baronetcy and a fortune. Belt, who was eight years Lawes’ junior, later set up his own studio and began to hoover up big commissions. When he won the contest to do the sculpture of Byron in 1877, the artists he defeated included Rodin.

Yet an increasingly envious Lawes had reason to believe that Belt didn’t make the Byron bronze himself. Not only did he not make it, he didn’t even design it. Both creative acts were reportedly performed by his assistant, the Belgian Francois Verheyden. When Lawes learnt that Belt had been commissioned by Queen Victoria to make a bust of Benjamin Disraeli, he couldn’t take it anymore. He joined forces with the editor of Vanity Fair and launched his offensive. Mr Belt, thundered the magazine in August 1881, was guilty of a “monstrous deception”. While presenting himself as a “heaven-born genius”, he was in reality “a purveyor of other men’s work, an editor of other men’s designs, a broker of other men’s sculpture”.

Soon afterwards, Lawes picked up the cudgels, stating in the magazine that his dearest wish was to “meet Mr Belt and his ‘influential friends’ in a court of justice”. His wish was granted. Belt sued and the trial commenced. The climax occurred when Lawes’s lawyers played their trump card. They gave Belt a block of marble, and told him to go into a side-room and make a sculpture. Specifically he was asked to copy one of his own works, a bust of an Italian named Pagliati. When Belt returned with the result of his labours, some at the back of the court applauded. However, the president of the Royal Academy, Sir Frederic Leighton, was less impressed. Called as witness, he dismissed the new bust as “grimacing” and “coarse and puffy”. Undaunted, Belt retaliated with a trump card of his own. He produced Signor Pagliati himself, and Leighton was forced to concede that it was a decent likeness.

No mere Victorian curio, this fascinating trial brings sharply into focus the perennial question of who gets to judge the quality of the art. The defence called a host of artists, including Leighton, Millais and Alma-Tadema, all of whom declared that Belt was a rotten artist. Belt’s lawyer countered by quoting Aristotle to the effect that “the public are better judges of works of art and literature than the artists and men of letters themselves”. The judge agreed. It was one of those sporadic moments at which a non-expert takes umbrage at the very idea of expertise. The jury deliberated. Then they delivered their verdict: in favour of Belt. Not only that, but they awarded him £5,000 in damages (£500,000 in today’s money).

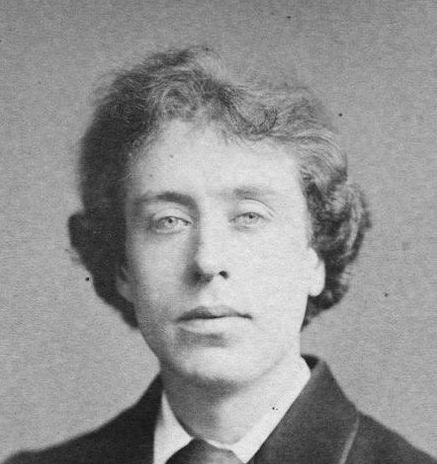

But who had won, really? Was it a victory for the working man over the gate-keepers of the art world? Or a victory for the philistines over the experts? The trial was over but the debate wasn’t. Lawes, naturally, was outraged and appealed against the verdict. But to his dismay, the appeal court decided the damages had been too small. It doubled them to £10,000. Although he was supported by family money, Lawes preferred to go bankrupt than cough up. As a result, Belt too went bankrupt. And it was then that events took a bizarre turn. Journalists at the time dubbed Belt “the Whitechapel Oscar Wilde”, not only because he physically resembled the playwright, but also because, with his long hair and easy charisma, there was something rather louche about him.

This was borne out a year or two later when, in desperate financial straits, Belt used his charms of persuasion to swindle one of the bigwigs to whom he owed money, a man named Sir William Abdy. Belt knew that Abdy’s wife, Marie Theresa, was fond of jewellery. So he approached him with an elaborate scam. He said that a friend of his, one “Mrs Morphy”, had been mistress to a certain Sultan and had received from him some magnificent jewels as proof of his love. Now she was in financial difficulties and wanted to sell the treasures but was embarrassed. She had asked Belt to help, so Belt had come to Sir William. Would he be interested in snapping up some priceless gems for far less than their actual worth? The gullible aristo agreed.

Belt sent his brother Walter to the nearest pawnbrokers to buy some inexpensive baubles for a song. These were presented to Sir William who gladly handed over many times their worth. Marie Theresa was delighted — or at least, she was until she spotted a photograph of another woman wearing identical jewels. This, she wrongly concluded, must be her husband’s mistress and she kicked up a stink. The matter was investigated and the tortuous truth came out. Richard Claude Belt, sculptor to the stars, was a grifter. He was sentenced to a year in prison with hard labour. After the judge delivered the verdict, Belt began to protest it was all the fault of Charles Lawes. The judge interrupted him: “No, no. Take him down. Not a word after sentence.” Belt did his time at Holloway Prison in North London.

And here we come to yet another twist in the tale. Before his downfall, Belt had received a commission to create a replica of the rather pompous statue of Queen Anne that stood outside the entrance to St Paul’s Cathedral. The original marble sculpture, made by Francis Bird in 1712, had been repeatedly vandalised, as well as eroded by weather. Another was wanted to replace it. Work had begun before Belt’s sentencing and apparently continued after it. Did his assistants finish the job, or was, as some have suggested, the new statue somehow smuggled into the prison so that the jailbird sculptor could chip away at it? All we know is that the second statue was completed and still stands in one of the grandest spots in London. If you visit it, you notice that a plaque on one side attributes it to Francis Bird, not mentioning Richard Belt. The latter is a black sheep of British art, airbrushed out of history.

The Byron bronze, with its disputed authorship, is now screened by foliage. The underpass that once allowed access has long been blocked off. His Queen Anne statue doesn’t deign to acknowledge him. The Draper’s Hall, where his Hypatia sculpture now resides, is rarely open to the public, guarding its statue like a secret. However, you can request a tour at [email protected] to get a glimpse. We’ve recently been reminded that public sculptures are among the most controversial of artworks. In Bristol, the statue of Edward Colston was dismantled by an angry mob. In Stoke Newington, the new tribute to Mary Wollstonecraft has been mocked as a travesty. But remember Belt. His trial, and the passions it stirred, show this kind of outrage is nothing new.