‘The woes of painters!’ lamented Edward Lear in a letter to a friend in 1862. Earlier that day, he was pottering around his apartment in Corfu Town, when, glancing out of the window, he spotted a troop of soldiers marching past. One of them, a certain Colonel Bruce, spied Lear and saluted. At which, forgetting he had a clutch of paint- brushes in his hand, Lear saluted back — ‘& thereby transferred all my colours into my hair and whiskers, which I must now wash in turpentine or shave off’. As a cameo, it sums him up. In that age of pomp and protocol, he always had (or felt he did) paint in his bushy beard.

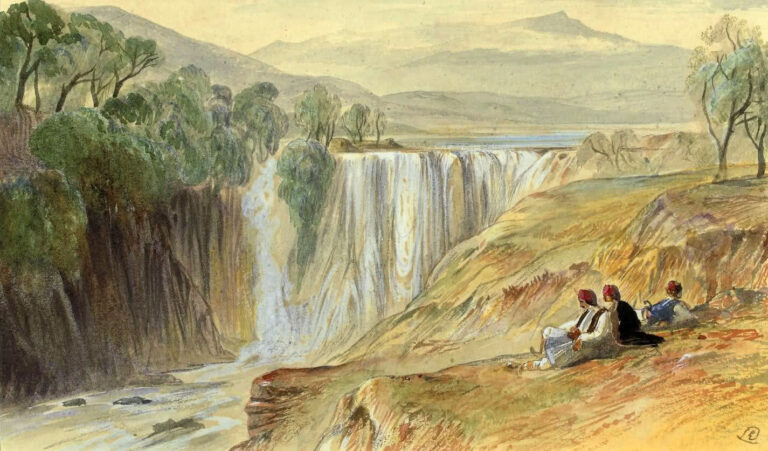

Edward Lear could hardly have chosen a worse time to live than the Victorian era, or a better place to lurk than this island of Corfu off the north-west tip of Greece. Corfu was (and is) beautiful; a painter’s dream. And now, for those who get the chance to see it, there’s a fine exhibition of Lear’s work on at the Palace of St Michael and St George, at one end of Corfu Town’s esplanade. The show marks the bicentenary of Lear’s birth, and Corfu grandees have made a point of going along to help celebrate.

This is just the kind of thing to have struck panic into the heart of the man himself. Lear was an outsider to his arteries. Born in Holloway, the 20th of 21 children, he was given up by his understandably exhausted mother to be raised by his older sister, and he never, some say, got over the sense of rejection. Plagued by bouts of depression, which he called The Morbids, and painfully shy about his appearance (fat, balding, bulbous-nosed), he scarcely felt fit for society half the time; the other half, he felt society wasn’t worth being fit for. In Corfu, he shunned the social life that occupied most colonials. The wife of one governor, Lady Young, came in for special criticism for her tedious triviality, as did the Marchioness of Headfort, whose fist- sized diamonds, Lear said, ‘cover her up so much that few people have seen their wearer’. He was pleased to relate how this same Lady Headfort had happened to be sucking on an orange as she entered the Church of St Spiridon, the island’s patron saint. A beggar-woman approached, palm thrust forward. When the bejewelled aristocrat claimed to have no coins, but offered her half-sucked orange, the disgusted beggar flung it back at her, before scarpering.

Here, in a nutshell, is the essence of Lear’s humour: a meeting of convention and chaos. In his verse and art, he suffused the mixture with real feeling, and a whiff of sentimentality. According to the distinguished biographer Michael Montgomery, Lear wasn’t gay (this I accept); he was a secret romantic who fell in love twice during the three years he spent on Corfu, and longed to marry. This I don’t quite buy. More likely, it seems to me, he didn’t want marriage, knowing himself too strange and set in his ways, but wanted to want it. Which accounts for his misty view of matrimony, a fine but always distant prospect. Heaven, he writes in 1862, should involve ‘a park & a beautiful view of sea & hill, mountain & river… a few well-behaved cherubs to cook & keep the place clean, &, after I am quite established — say for a million or two of years — an angel of a wife’.

Through this prism, his best-known poem, ‘The Owl and The Pussycat’ (1867), comes to seem a bachelor’s daydream (‘Come let us be married,/ Too long we have tarried…’), penned, perhaps, after a couple of glasses of port. Lear clearly is the owl. But where was the ‘beautiful pussy’? She didn’t exist, and he knew it.

Yet solitude has its consolations. In his case, these included the space to develop his extraordinary personality, which still gives pleasure today, through his paintings, his verse, and for those who seek them out, his excellent letters and journals. Early in 1864, as the British were ejected from Corfu, Lear packed up his possessions to vacate his paradise island. In a letter to his friend Chichester Fortescue, he struck, as so often, a delicate balance of humour and melancholy. ‘Goodbye,’ he wrote. ‘My last furniture is going. I shall sit upon an eggcup & eat my breakfast with a pen.’